Hagius: Architecture as a Medium for Wellbeing

- Name

- Hagius

- Images

- Clemens Poloczek

- Words

- Valerie Praekelt

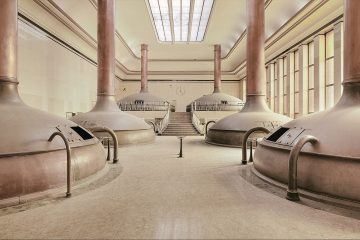

Berlin’s vibrant Torstraße in Mitte isn’t exactly a street you’d associate with the words “calm” or “retreat”. Yet, from the moment you step into the sports studio Hagius, housed in the historic former post office building, the noise of the city immediately fades away. There’s a sensitive and balanced feel to the space, which was founded in 2020 by brothers Nicolas and Timothy Hagius, who wanted it to be a little more than just a “gym.”

In a way, of course, it is, but at its core, it’s more of a multisensory playground for strength training and Pilates practice. The studio was architecturally brought to life by Gonzalez Haase AAS. Pierre Jorge Gonzalez and Judith Haase, internationally celebrated for their crisp, timeless approach, have designed retail spaces for luxury houses such as Balenciaga and Aeyde, as well as galleries like Thomas Schulte. At Hagius, they decided to let the materials speak for themselves: the entryway is defined by granite stone and white-lyed solid ash; the workout areas are shaped by natural rubber, linen textiles, and stainless steel. Additionally, Gonzalez Haase AAS architects worked with biodynamic lighting, which can help to stabilise the human biorhythm and subtly synchronise it with periods that differ from our internal clocks. This approach naturally raises a question: can good design really create spaces that match our natural rhythms and influence both body and mind? Timothy Hagius, co-founder of the eponymous sports studio, certainly thinks so. He believes that when design is truly working, it doesn’t announce itself—it quietly supports the experience from the background.

"We wanted a studio where training sits at the center, elevated by its surroundings, not overshadowed by them."

Timothy, I first came across Hagius through the architects at Gonzalez Haase AAS. I’d written about their work before, and their take on a gym caught my interest. Why did you want to work with them?

They understand that architecture’s primary task is not to decorate a function, but to create the right atmosphere around it. Gonzalez Haase come from designing art galleries and museums, spaces where architecture must quietly support a core experience rather than compete with it. Their work is never about bright colors or bold statements, but about proportion, light, materiality, and restraint. That sensitivity to atmosphere, to how a space feels before you consciously register it, was exactly what we were looking for: We wanted a studio where training sits at the center, elevated by its surroundings, not overshadowed by them.

Shortly after you opened, I interviewed Judith and Pierre Jorge, and asked them about their idea for Hagius. Judith responded straight away: “The Hagius brothers already had the vision—we just had to bring it to life.” What was that vision?

To design a space with intellectual depth, one informed by scientific knowledge about health, perception, and human rhythm. From the beginning, our goal was simple but strict: People should feel better after every visit. To achieve that, we had to define a very precise atmosphere. Every design decision was made with an understanding of how it would affect the nervous system, focus, and recovery. For us, design is not decoration; it is a wellbeing function. We truly believe that it’s not only about moving correctly, but about moving correctly at the right time, in a space that actively supports the body rather than working against it.

Often, we only talk about spaces when they are brand new. Hagius recently celebrated its sixth year—what architectural features still make sense to you?

Almost all of them, which is the best possible outcome. The clarity of the spatial layout, the material choices, the lighting logic, these are things that don’t age quickly. We didn’t design for trends, but for longevity. If anything, the space has become more relevant over time because it was never tied to a moment but to human behavior and physiology.

"Today, you can point to almost any element in Hagius, and there is a reason behind it..."

You have a background in opera. Why did you want to open a sports studio?

I was fortunate to be exposed early on to very different creative disciplines, opera, music, stage design, and performance, all of which are deeply concerned with atmosphere, timing, and the way environments shape human perception. What fascinated me most was not the spectacle but the rigor behind it: the invisible decisions that allow expression to unfold with clarity and intention. When I returned to Berlin, I realized that this depth was largely absent in spaces dedicated to health, even though these are the spaces that influence us most directly. I wanted to translate that intellectual and atmospheric precision into a sports studio. Today, you can point to almost any element in Hagius, and there is a reason behind it: from the absence of visible sockets, to hidden fixings to a specific shade of grey chosen for how it reflects light and subtly aligns with the body’s biorhythm. That depth of thought was something I deeply missed. I believe that health should not be transactional or utilitarian; it should inspire, cultivate awareness, and become something people actively choose to live for.

How did you want to reinvent a sports studio in terms of design?

The dominant trend has been to impose a specific atmosphere: dark rooms, loud music, red lighting, environments that deliberately stimulate and stress the nervous system. What concerned me was that this approach is rarely questioned. We already place stress on the body through training, yet we often add another layer of sensory stress without asking whether this actually supports long-term health. Our approach was the opposite. We wanted to align all senses and reduce unnecessary external stress through the architectural shell, so that the body can direct its energy where it matters most: into movement, technique, and adaptation. By carefully calibrating light, sound, materiality, and spatial clarity, we created conditions in which training becomes more productive and more effective.

You work with biodynamic lighting – what effect does this have at Hagius?

Biodynamic lighting supports the body’s circadian rhythm by subtly changing intensity and temperature throughout the day. It’s not something people actively notice, but it is something they feel. It helps regulate energy, focus, and recovery, and prevents overstimulation, especially in a training environment. Architecture in general influences the nervous system long before conscious thought begins. Ceiling height affects breathing, acoustics influence stress levels, and light impacts hormonal balance. When these elements are calibrated correctly, the body relaxes faster, movement quality improves, and recovery begins earlier, even within a short visit.

Torstraße is extremely loud. Whenever I step inside Hagius, that noise instantly disappears…

The transition from street to studio is part of the experience. Acoustic insulation, spatial buffering, and material choices were designed to create an immediate sense of separation. It’s a threshold moment, leaving the city behind and arriving in a space that allows for concentration and physical presence.

Your guests only stay for about an hour and a half. What does a room need so people feel good instantly and want to come back?

Clarity, coherence, and trust. The body reads a room within seconds. If the space feels calm, legible, and intentional, people relax immediately. There’s no need to impress, the goal is to feel right.

You focus on strength and Pilates. In fitness, strength has become a buzzword. What does it mean to you?

Strength is about capacity. It’s not just muscular, but structural and mental. Proper strength training supports longevity, posture, metabolism, and confidence. Combined with Pilates, it creates balance: power with control, effort with awareness––that combination forms the foundation of long-term well-being.

"Design should support life, not replace it."

Design can be intimidating. Is there a danger of losing authenticity when spaces become too perfect?

Yes, that is a real risk, and we were careful not to create a sterile or museum-like environment. A space becomes authentic through use, through people moving, sweating, returning. Design should support life, not replace it. Warmth, restraint, and human scale are essential to keeping a space welcoming.

ADDRESS

Hagius

Torstraße 105

10119 Berlin

Germany

CONTACT

Website

Images © Clemens Poloczek | Text: Valerie Präkelt