Worlds Between Water and Waste: Leeroy New at Futurium’s Ocean Futures

- Name

- Leeroy New

- Project

- Ocean Futures

- Images

- Stefanie Loos

- Words

- Anna Dorothea Ker

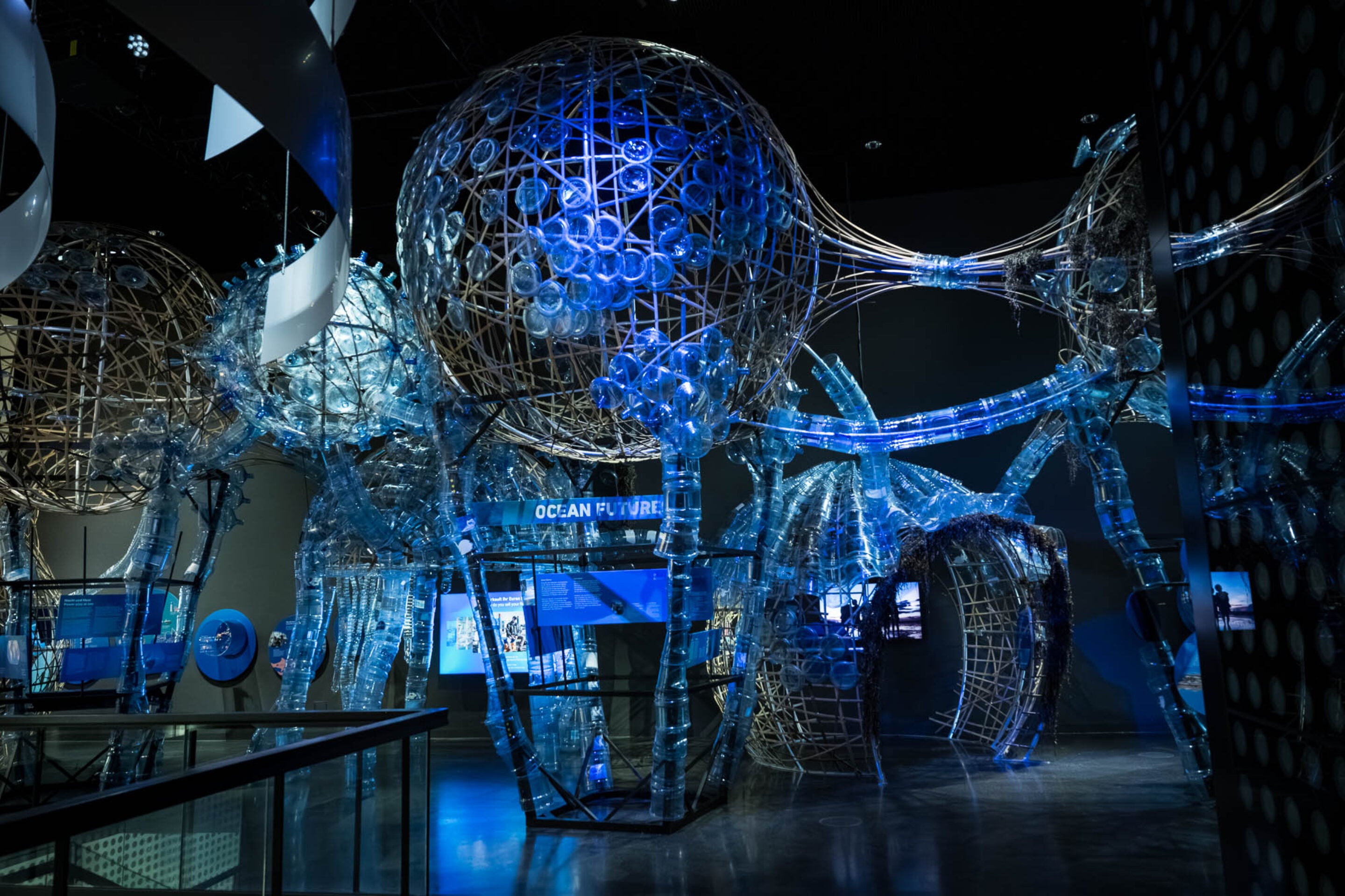

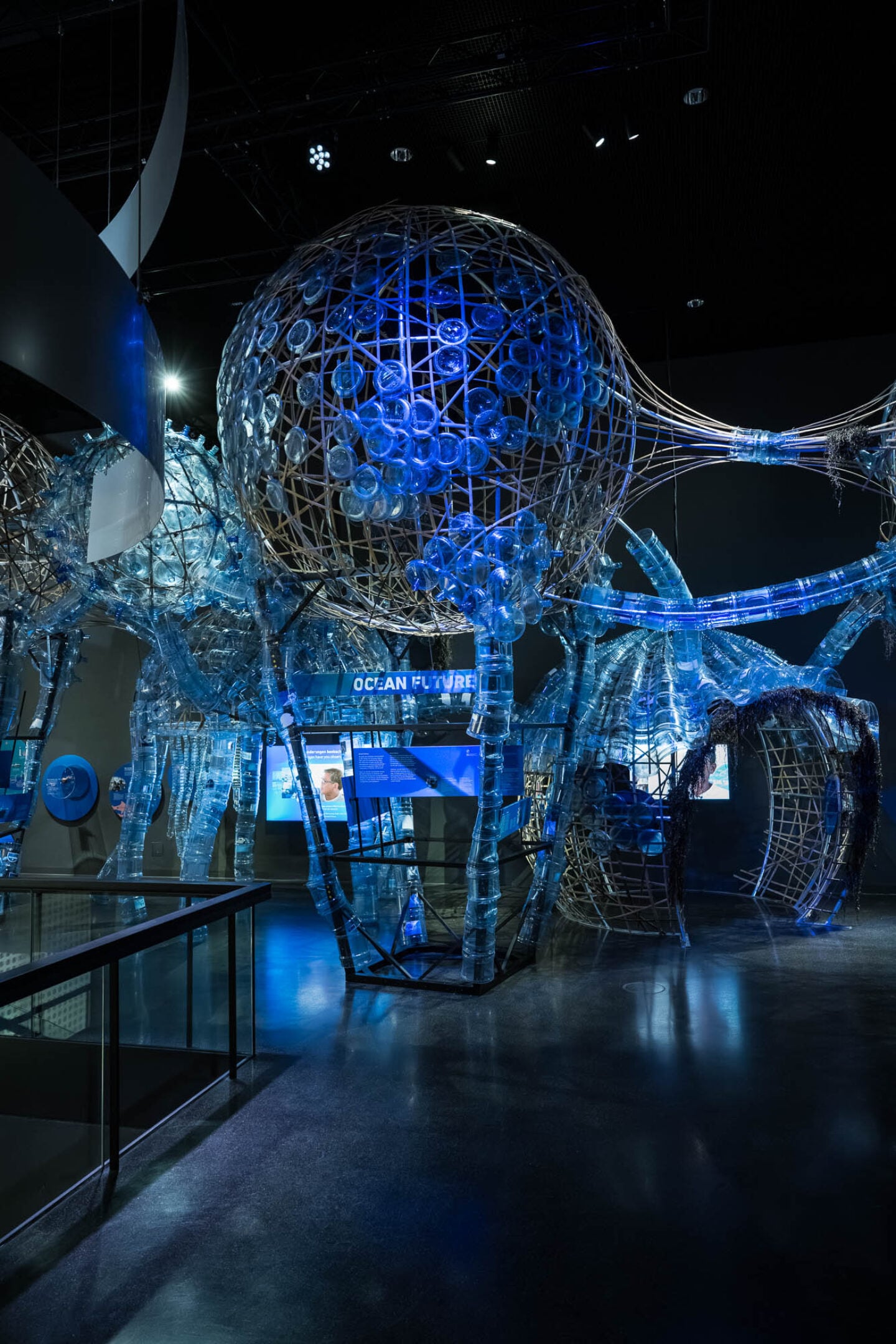

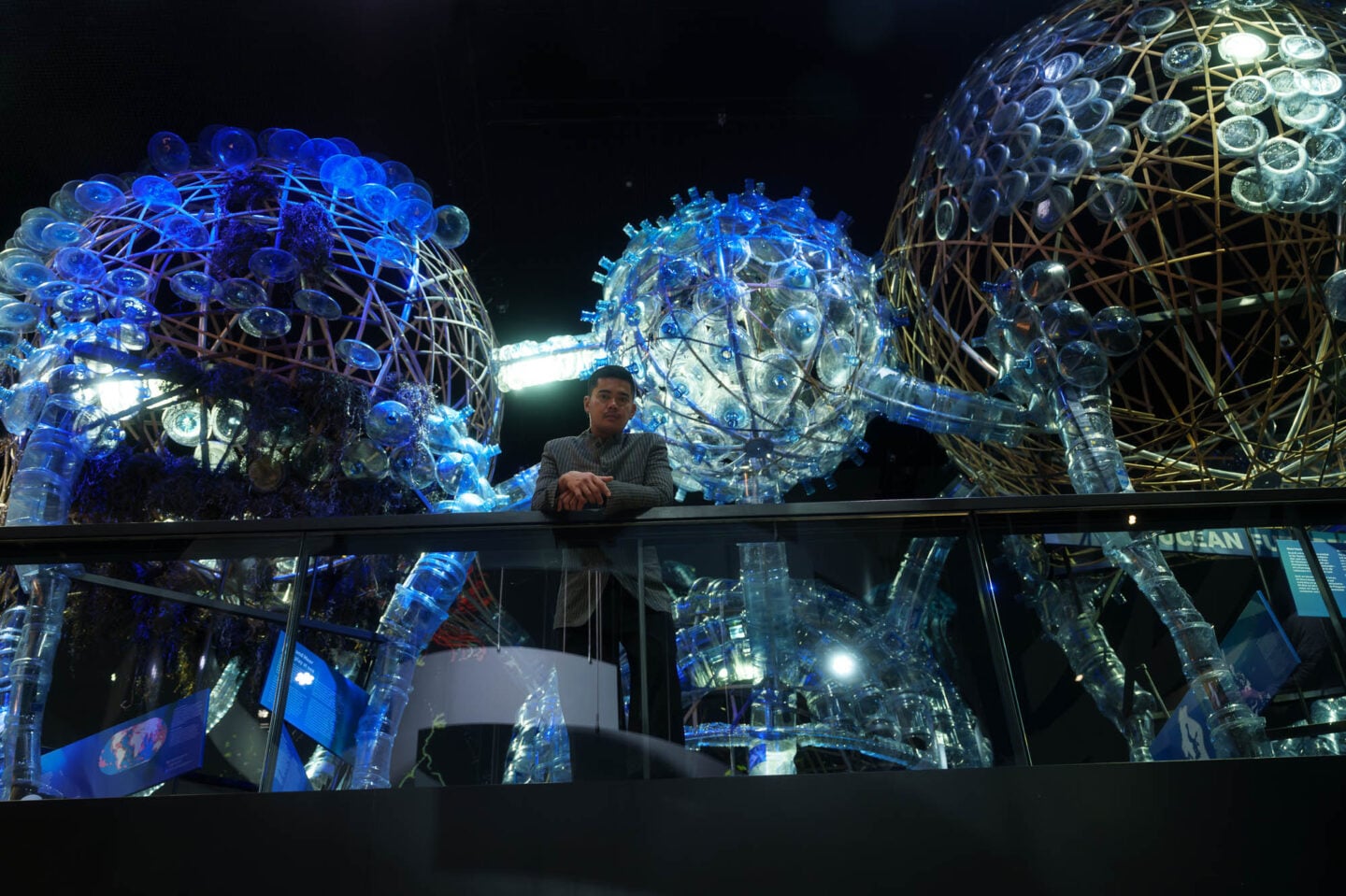

At Berlin’s Futurium museum for futures thinking, the exhibition Ocean Futures (on through 31 August 2026) navigates the planet’s vast expanses of water as infrastructure, archive and neighbour. At its centre stands Filipino artist Leeroy New’s installation Balangay Spacecraft—a colony of interlinked spheres forged from bamboo and recycled plastic—part mangrove, part artificial island, a future habitat taking root on shifting ground.

The spheres act as walk-in chambers: womb-like rooms for transformation and growth, attentive to nourishment and rebirth. Vessel is both form and function here. Balangay, an ancient wooden watercraft once used across the Philippine archipelago for trade and migration, becomes New’s scaffold for collective space-making. This speculative architecture equally performs practical work: as a platform for learning, listening and civic exchange. In conversation with Ignant, Leeroy reflects on building with the detritus of global consumption, and on rethinking belonging and kinship amid rising seas.

Image © Stefanie Loos

Image © Stefanie Loos

Leeroy, thank you for sharing your story with Ignant. This commission of your work Balangay Spacecraft, the centrepiece of the exhibition Ocean Futures, marks the first special installation at Futurium. How did you approach the brief, and what initially drew you to it?

I was invited after Gabriele and Rosalina [ed’s note: Futurium’s Dr. Gabriele Zipf, Head of Exhibitions and Dr. Rosalina Babourkova, Research Associate] connected with the Mind Museum in Manila, a long-time collaborator of mine. They commissioned me to create a new version of my speculative Philippine sci-fi structures—Mebuyan’s Colony and Mebuyan’s Cradle, a series of works that has evolved over the years.

For context, Mebuyan is a pre-colonial goddess of death and fertility from the Bagobo tribe in the Philippines. We have so many languages and over 7,000 islands, so this is just one of many stories that were repressed during 300 years of Spanish colonisation and 50 years under American rule.

I try to integrate these stories we’ve been deprived of for so long—stories that look towards nature and towards these powerful goddesses who control life and death, who are celebrated for bountiful harvests and for nurturing life. The structures in this series feature clusters of orbs and spheres connected by bridgeways or by root- or branch-like forms.

Mebuyan is described as having breasts all over her body. On top of shaking a local lime tree—where the fruit that falls determines who dies—she also nurtures the spirits of dead children. Hence the body covered in breasts. These spheres or orbs in my works refer to that description of her, which Europeans at the time described as grotesque. They have also become interactive spaces that people can enter—womb-like places for transformation and growth, referencing nourishment and rebirth.

This has become an ongoing series. I’ve done several versions, sometimes integrating agricultural systems and working with farmers and gardeners to green them. Most have been in public spaces. This is one of the few times I’ve built something indoors, but I find it impressive that Futurium is still free to enter—so in that sense, it remains a public space.

“This work became a kind of personal challenge—to create active approaches to this surplus of plastic waste within a creative context.”

In what other respects does this installation advance the series and the conversations it engages?

Gabriele and Rosalina visited fishing communities in the Philippines to explore relationships between bodies of water and the people living near them. The show also includes fishermen and -women from the Baltic. I think it’s interesting to compare these different places—geographically and culturally distinct, but similar in the sense that both are targets of waste in various forms.

In the Philippines, as a developing country with a very dense population, we’ve become a destination for multinational products that come in plastic—without the infrastructure or education to deal with the resulting waste. We’re flooded with packaging and single-use items, yet we lack the systems to process what’s left over. There have also been many instances of non-recyclable waste being secretly shipped to countries like ours.

I grew up watching a lot of sci-fi, and my work became a way to participate in that conversation about where I, and where I’m from, might exist in the future. The stories of the future that I saw growing up were told from the perspectives of economic powers—Japan, Europe, America. At some point, while practising art and still being influenced by those films, graphic novels and books, I wanted to participate in transforming my own environment. I wanted to be part of these visions of the future I grew up admiring, but it was clear that we were absent from those narratives.

This show provides a platform for other perspectives and voices—to imagine a not-so-distant future where, yes, we continue to be recipients of waste products, but also where we try to reconcile that reality with our own agricultural and material resources. Bamboo, for example, offers a sustainable alternative to timber for construction. But at the same time, plastic is everywhere. We don’t have proper waste management systems, and we face huge problems with corruption—both in government and in cultural institutions. Waste is often neglected because officials claim there are more pressing issues. We’re still a young country, still in the process of development, still trying to purge deeply corrupt systems.

So this work became a kind of personal challenge—to create active solutions, or at least active approaches to this surplus of plastic waste, within a creative context. I try to give these discarded materials new, functional, and interactive forms. My sculptural practice has overlapped with inhabitable structures. I work with architects and bamboo innovators in the Philippines to offer alternatives, while bringing in our particular cultural sensibilities.

Our country never went through a traditional art-institution model of national museums or commercial art centres. Our art was part of our daily rituals long before colonisation, and so our sensibility is different. That’s why I gravitate towards public works and wearable pieces—things that inhabit public spaces and come to life through performance. What you’ll see here is an attempt to create a kind of future colony. The forms resemble clusters of domes connected by walkways—something that might appear on Mars—but my version uses what’s accessible: bamboo and plastic bottles.

In the Philippines, we don’t have potable tap water, even though we’re surrounded by the ocean and have over 7,700 islands. We rely heavily on bottled water, so we have an abundance of blue five-gallon jugs and PET bottles. I started my practice using found objects—even new materials bought from large market districts—turning them into alien forms. Over time, I began sourcing from recycling centres and sorting facilities. People connected with that approach, and it challenged me to work strictly with what’s available, only introducing new material when necessary for structural stability.

The installation combines natural and synthetic materials—bamboo and plastic. How did you approach sourcing them?

These days I work with what’s local. I visit second-hand shops, recycling centres, reuse facilities—we’ve completely stopped shipping materials. The resources required to produce large-scale works are immense, and traditional sculpture and casting already produce so much hidden waste.

A key aspect of the work now is starting the conversation early: learning where to source materials and understanding what’s available. Collaborators often realise how unique or challenging their local waste is to collect. I make a point of visiting sorting facilities in most of the countries I work in—not tourist destinations, but recycling plants. I’ve visited the one here too, and it’s fascinating to see the conveyor systems and how differently each country operates. Sometimes I’m allowed to take materials; sometimes they’re strict about not releasing trash. Either way, we always use what’s already there.

Bamboo, meanwhile, is easy to grow. It’s essentially a grass and grows incredibly fast with minimal maintenance. It’s part of a global movement as an alternative to timber. In Southeast Asia, particularly Thailand, Vietnam, and Bali, the bamboo architecture scene is far more advanced. In the Philippines, it’s only starting to gain momentum, so I’ve been learning from the architects who are leading that effort. I think this connects to a broader mentality in the Philippines—of looking outward and forgetting what we already have. We’re now trying to reclaim and relearn that knowledge.

We know recycling plastic isn’t a true solution—we have to find alternatives. My work brings together the natural and the synthetic. I can’t ignore the plastic around me and only work with bamboo. That tension—between natural and artificial—runs through everything I make. The result is what I think of as biosynthetic structures.

Could you share the meaning behind the title of your installation, Balangay Spacecraft and how it reflects your vision of the future?

Balangay refers to our ancient vessels. We’re a maritime culture—we travelled from one island to another, and there are expansive migratory routes that can be traced from North Asia and Taiwan all the way to the Polynesian islands. The word ‘barangay’, meaning village or community, comes from ‘balangay’. These two ideas—boat and community—inform each other.

I’ve expanded on that idea as a kind of vessel, a kind of spacecraft. Not necessarily for outer space, but a vessel that could hold emotional, mythical, or physical space. The colony becomes that vessel. I imagine them as satellite-like structures that may not look like boats but resemble interconnected pods joined by tunnels and bridgeways.

The goal isn’t to escape to outer space. These colony-like structures are built in many different areas across the Philippines. The largest one I created was through a Burning Man grant, built in a surf town four and a half hours from Manila. It was a major undertaking, especially since we rarely receive public art funding in the Philippines. The project was something that would never have happened through local government or commercial channels, where art is still primarily painting-driven and tied to the gallery market.

That structure became a landmark for the town. Locals have claimed it in different ways: a nearby turtle sanctuary sees the orbs as turtle eggs, and surf instructors tell visiting students to check it out. That’s what we want—for people to claim the work as their own in whatever way makes sense to them.

How do those local interpretations connect with the wider concerns of waste, climate and water in your work?

I recently visited island communities off the coast of Tubigon, Bohol [central Philippines], who are severely affected by rising sea levels. During high tide, water rises to their thighs. Houses are elevated higher and higher. Most people stay because they have nowhere else to go. I’ve also been working with Greenpeace to help bring attention to their situation through creative means. Even in cities, flooding is constant—three major typhoons in a week is not unusual. These events expose government corruption in flood control projects. Through social media, people are seeing this more clearly now, though change is still uncertain.

How did your interest in building imagined worlds evolve into a more collaborative and socially grounded practice?

I didn’t start out tackling these subjects. I just wanted to make art—large works, my own sci-fi world. But that led to very practical questions about building in a place where the city itself feels alienating to its people. Many of my collaborators are friends from art school, where we had performance majors. We began documenting bodies in strange, makeshift costumes in urban environments—people just trying to live. We’ve kept working together since. I create costumes and spaces, and they activate them through performance. It’s an ecosystem we’ve built together.

What does that look like specifically at Futurium?

On opening night, a live performance, Dance of the Underwater Creatures, will bring the installation to life. The performers, all from the Philippines, will appear like extensions of the work. They’ll wear specially designed costumes made from the same materials. This also extends the exhibition’s themes. Migration is deeply woven into our story. Everyone has a family member who has had to leave the country to make a living, and that ties back to how, even though the Philippines is a rich and resourceful group of islands, the systems embedded through our history make it unsustainable to live and work there.

We don’t have long winters to prepare for. European colonisers once accused us of being lazy—of just waiting for fruit to fall from the trees—because our climate is rainy and sunny, and food is abundant. But their economic systems and market structures were imposed on our way of life. So even though we have land and natural resources, we still need to seek work abroad. That’s why it’s meaningful that the five performers activating the work here are all Filipinos based in Berlin.

“Playfulness feels true to how we deal with things back home. Even in the middle of floods and other crises, people find ways to laugh. It’s part of how we process hardship—you either laugh or cry.”

What kinds of questions do you hope the exhibition might spark for visitors?

It’s hard to say, but I’ve been observing people’s reactions as the installation takes shape. At first, it was just bamboo, and people were intrigued by this flexible wooden material they didn’t recognise. When the plastic cladding started to appear, curiosity grew. I like that—when people first see something alien, then realise it’s made from familiar, domestic objects. That humour, that playfulness, feels true to how we deal with things back home. Even in the middle of floods and other crises, people find ways to laugh. It’s part of how we process hardship—you either laugh or cry.

The exhibition Ocean Futures featuring the installation Bangalay Spacecraft by Leeroy New is on view until 31 August 2026 at Futurium in Berlin. Futurium is open Friday to Monday from 10:00 to 18:00, and Thursday until 20:00. Entry is free.

Photography (exhibition): Stefanie Loos | Interview: Anna Dorothea Ker | Curators: Futurium in cooperation with The Mind Museum Manila | Artist: Leeroy New