Q&A: Viviane Sassen on the Body as Symbol, Surface, and Story

- Name

- Viviane Sassen

- Words

- Anna Dorothea Ker

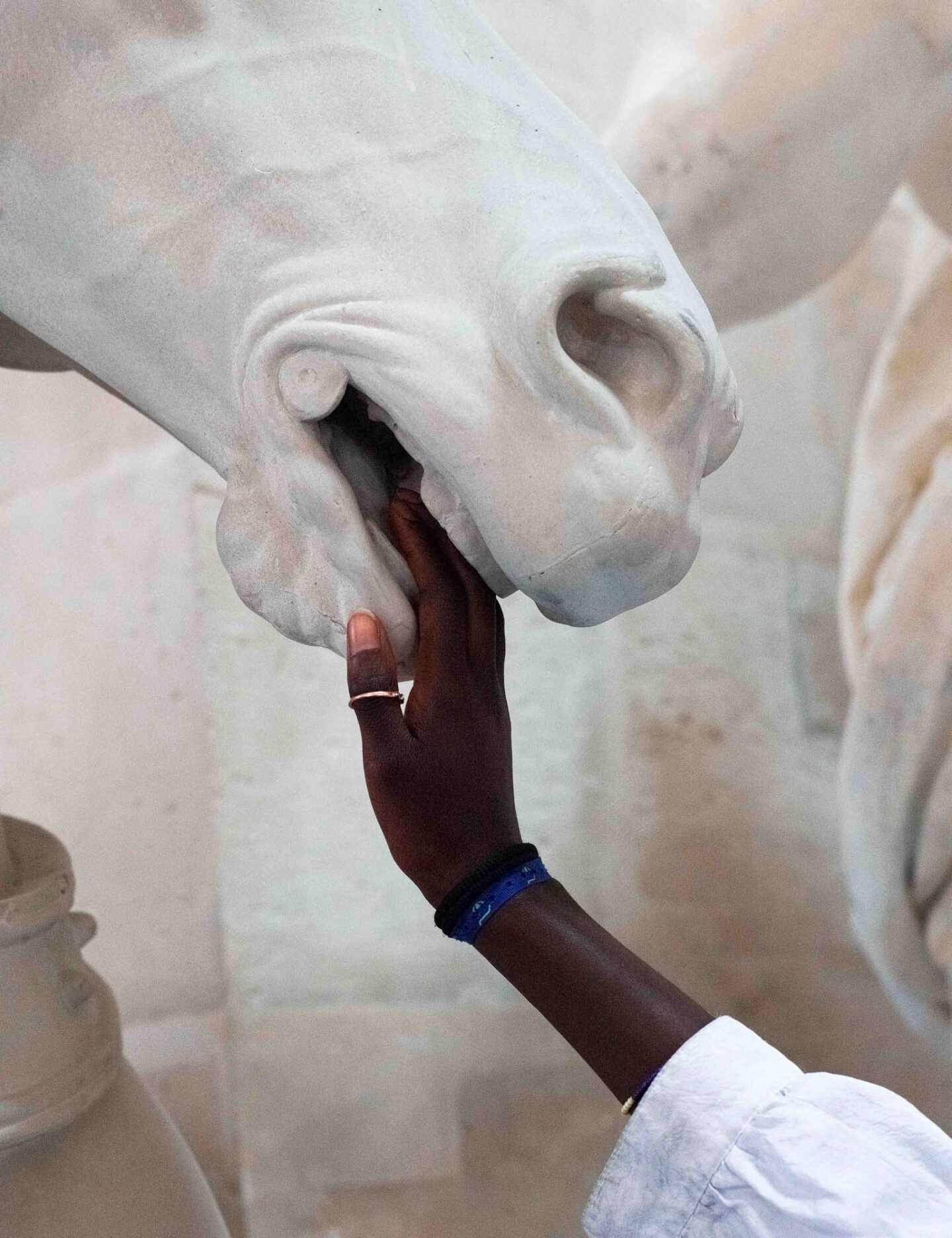

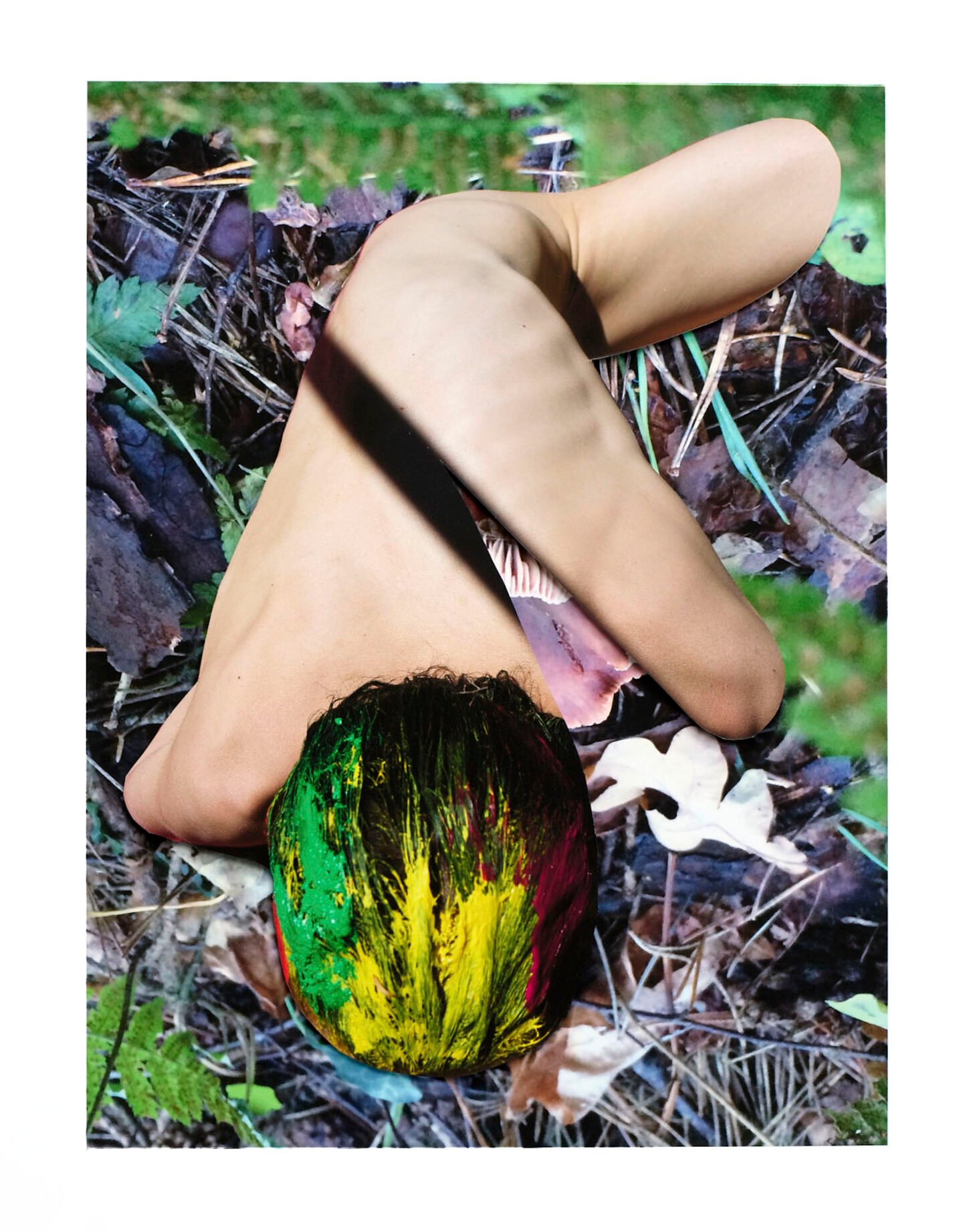

Over the past three decades, Dutch artist Viviane Sassen has carved a singular path through the intersecting worlds of photography, fashion, and contemporary art. Known for her bold compositions, charged use of color, and intuitive treatment of the human form, Sassen has developed a visual language that resists easy categorisation. Her work is at once sculptural and intimate, conceptual yet visceral; often playing at the edge of surrealism while remaining connected to the body and its many expressions.

At Fotografiska Berlin, The Body as Sculpture (on through 8 June 2025) brings together works from across Sassen’s expansive archive. Its thematic presentation foregrounds her enduring fascination with the body, as a subject and a site of transformation. Encompassing self-portraits, sculpture and surrealist collages, the exhibition unfolds as a focused exploration of corporeal abstraction, memory, and desire.

Sassen’s early exposure to sickness, death, and physical difference—growing up in Kenya, where her father worked as a doctor—was formative, and continues to inform her visual approach today. In her images, beauty is never fixed; the gaze is never neutral. Her portraits defy conventions of symmetry or seduction, often concealing faces or interrupting the body’s legibility. Whether shot on fashion sets or reassembled in collage, her subjects become vessels—of longing, power, and mystery.

In conversation with Ignant, Sassen speaks candidly about her practice, from her early self-portraits to her reflections on representation, ritual, and the unknown. Her work eschews conclusions, inviting the viewer into a shared space of ambiguity—where what is hidden is just as telling as what is seen.

"Together with curator Marina Paulenka, I decided to create a new concept—a new show based on the body."

The Body as Sculpture brings together some of your most compelling images that align the human form with abstraction. How did the idea for this exhibition come together?

The initial idea was to bring my exhibition PHOSPHOR to Berlin, which is a retrospective of the past 30 years of my practice. However, the space at Fotografiska Berlin wasn’t large enough to show the entire exhibition.

So, together with curator Marina Paulenka, I decided to create a new concept—a new show based on the body. As the body has always played a significant role in my work, both as an artist and in my practice as a fashion photographer, I was still able to show work from various phases of my archive.

In that sense, this exhibition is also an overview of 30 years of work—but concentrated on one theme. I find the very early work I made during and just after my studies particularly important. Those images show the seeds of what came after; you can clearly see the links between the early work and the work I made later.

You often explore identity and the body in ways that challenge conventional notions of beauty. Is there a particular cultural or personal experience that’s been a major influence on your exploration of these themes in your photography?

I think I’ve been intrigued by the body from a very young age. I spent some of my most formative years in Kenya, where my father worked as a doctor in a small local hospital. This was in the mid-seventies, and things were much less advanced than they are now.

Sickness and death were more visible, more out in the open. Decay also moves much faster in the tropics—a banana peel would rot and disappear in a matter of days rather than years.

Another experience that made a big impact on me at the time: we lived next door to a home for children with polio. I was too young then to understand the seriousness of their conditions. I thought the deformations of their bodies were maybe a bit unusual—but also beautiful.

You’ve spoken about your desire to create a sexuality that resists the male gaze. How do you approach a shoot to ensure the gaze feels layered and fragmented, rather than something to be consumed?

I think that’s something much more embedded in the subconscious while I shoot. It’s not so much a clear thought or concept that sits at the forefront of my mind while making work. When you censor yourself in the process, you can get caught up in frustration—whereas I prefer to create an atmosphere of complete freedom to explore and play.

It does help to have an all-female crew. I think it’s wonderful to have a creative process with like-minded women, without male influence or energy. The vibe is more relaxed, and it enhances the feeling of sisterhood—which I really value.

Having been both a model and the one behind the lens, what does documenting yourself allow you to explore in terms of how the body is presented?

It’s been a long time since I made self-portraits—I created them in my late teens and early twenties. Often it was a way to explore multiple elements at once: to look at my body from different perspectives. Sometimes very formally or abstractly, focusing on shape, line, and the surface of skin.

Other times more culturally, thinking about how my body appeared to the outside world, to the male gaze, or within the context of fashion. And finally, it was personal—even sexual—as I was still exploring my own desires and first relationships.

“Disguise has always been linked to some form of desire in my mind.”

Your work often plays with the viewer’s expectations, revealing just enough to intrigue but never fully exposing. How do you navigate the tension between showing and concealing?

I think disguise has always been linked to some form of desire in my mind. It’s crucial to both hide and reveal in order to trigger longing—there should be some mystery. For instance, in my more sexual or erotic images, you often won’t see a face.

We’re conditioned by language, by meaning, by image and symbol. But when it comes to desire, we also need the unknown—the thing we can’t quite grasp.

The surrealist elements in your work allow the body to transcend its physicality. How do you see the body as more than just a material form—what can it become when altered or reshaped through photography?

I think the body and its materiality can speak to hidden stories of transformation—things we’re unable to see, as they’re non-physical—by showing the exterior, the surface. The body in motion or adorned, or in the case of my collages, dissected and rearranged, can reflect an internal shift into the outside world.

You see this in fashion, in costume, carnival, and in ancient ritual dances. The body becomes more than the individual—it becomes symbol, mythology, story. For me, surrealism has always been a powerful tool to visualize that process.

"The collages allow me to go beyond the frame—they can float in space, even become three-dimensional."

How does the collage element of your practice inform your other types of image-making, particularly when it comes to constructing or deconstructing the body?

The collages allow me to go beyond the frame—they can float in space, even become three-dimensional. The photographic medium is often less flexible, especially when you think about analog photography, no Photoshop.

Working with tactile elements—not digital—gives me more freedom to explore scale, material, and dimension. I’m not sure how that has informed my other work, but I’m sure it has, in a subconscious way.

If you could revisit any of your past series, which one would you choose? How would you edit or expand it differently now?

I think I’d like to return to the early work I made in Africa in the early 2000s. I still stand behind that work—it was very honest and personal. But I’ve also grown older and less naïve. I felt it was necessary to educate myself more around identity politics, cultural representation, and so on.

It could be interesting to revisit that work at some point—or to make new work based on those early series.

Is there something or someone you haven’t yet photographed that you’d like to?

Oh, there are so many things I’d love to stick my nose into—I’m a very curious creature, and the world is so big…!

Viviane Sassen: The Body as Sculpture is on view at Fotografiska Berlin until 8 June 2025. The museum is open daily from 10:00 to 23:00, with last entry at 22:00. Plan your visit here.

Images © Viviane Sassen | Text: Anna Dorothea Ker | Intro image by: Keke Keukelaar