Unbuilding Walls: The German Pavilion At The Venice Biennale

- Name

- Graft

- Project

- Unbuilding Walls

- Images

- Daniel Müller

- Words

- Rosie Flanagan

This year marks a strange moment of historical symmetry for Berlin — the inner German border that divided the East from the West (1961-1989) has now been down for as long as it stood. It seems pertinent timing then for ‘Unbuilding Walls’, the German Pavilion’s contribution to this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale.

Curated by Graft Architects — Lars Krückeberg, Thomas Willemeit, and Wolfram Putz — alongside Marianne Birthler, the former Federal Commissioner for the Stasi Records, ‘Unbuilding Walls’ looks closely at the spatial and psychological impact of walls, and the policies of division and exclusion that they enable. “It is a conscious look at the world today, and at the dangers of breakdowns in communication,” Putz explains of the exhibition’s intent. “We wanted to illustrate just how easily these walls can be constructed — which is why we are looking at the unbuilding of walls. Our inbetween message is that it’s not over when you call in the demolition team, unbuilding takes a long, long time.” Today, as vitriolic othering is used to mobilize everything from Trump’s wall to Brexit, the history of Germany’s inner wall illustrates the danger of ceding to populist thought on national division in a tangible way.

Though Willy Brandt’s famous proclamation, “What belongs together, will grow together”, has proved itself mostly true, the garden has not flourished as easily, nor perhaps as quickly, as anticipated. Despite 28 years of reunification, the city still shows signs of separation and certain sentiments — like die Mauer im Kopf — endure. A study by the Berlin Institute for Population and Development concluded that half of all Germans believe there are more differences than similarities between those from the East, “Ossis”, and those from the West, “Wessis”. This psychological divide reflects persistent economic, political, and socio-cultural differences between the East and West. Statistically, East Germans earn 20 percent less, own 50 percent less property and have 50 percent less savings than their West German counterparts. They’re also less likely to occupy seats of power within both businesses and parliament.

"When a deadly border runs through a country, it is in effect a giant wound."

“No-one could know in the joyful days after the fall of the wall that its legacy would take not just years, but generations to overcome”, explains Birthler. “And no-one should expect that at some point it will disappear from our collective memory, that we can make it undone. When a deadly border runs through a country, it is in effect a giant wound. This wound has been healing now for 28 years, but very slowly… Scars will still remain.” Since its fall in 1989, the border and accompanying death strip that zigzagged through the city has been built over: its history architecturally memorialized, monetized and forgotten in equal parts. Is this what Brandt meant when he said he hoped for a country grown together?

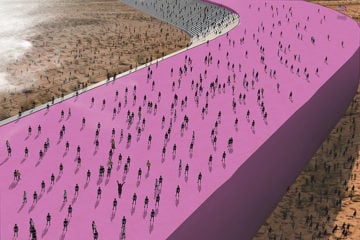

Drawing upon the parallel between the site of the former wall and “Freespace” — the theme of this year’s Biennale — the German Pavilion explores the effects of division, and the long process of healing as both an architectural and social phenomenon through an international prism. “After 28 years it was time to look back to see what happened after the wall fell down,” Krückeberg tells us, “It’s not just about the wall, it’s about what happened to the country, and what happened to the space. How did we deal with it? Did we come together again, and in what way? What were the strategies, and what is the status now? It was always clear that this project could not be limited to architecture, it had to deal with society. You cannot separate one from the other — if we had, the exhibition would have surely failed.” In considering both the architectural and the human, the German Pavilion presents 28 sites: 22 architectural interventions in the space left by the wall and the adjoining death strip, and in a separate video installation, six of the most famous walls that divide spaces around the world with commentary from those who live beside them.

'Unbuilding Walls': Inside The German Pavilion

All exhibition images © Jan Bitter

After the wall came down in Germany, the natural inclination was to raze it from both public land and memory: 28 years on, and the country is still negotiating this space. There has been no overarching policy that governs the site of the former wall and death strip, no legislation that dictates precisely how it must be dealt with spatially. It is from the resultant architectural cacophony that Graft and Birthler have selected the sites on show at the German Pavilion. Described by Willemeit as a collection of voices and attitudes, of ‘Unbuilding Walls’, he explains: “You can see it as a 28-year-long measurement of the debate with its majorities and its minorities, with its niches and its power struggles. It’s also symbolic of the way that the republic works — there was no top-down message.”

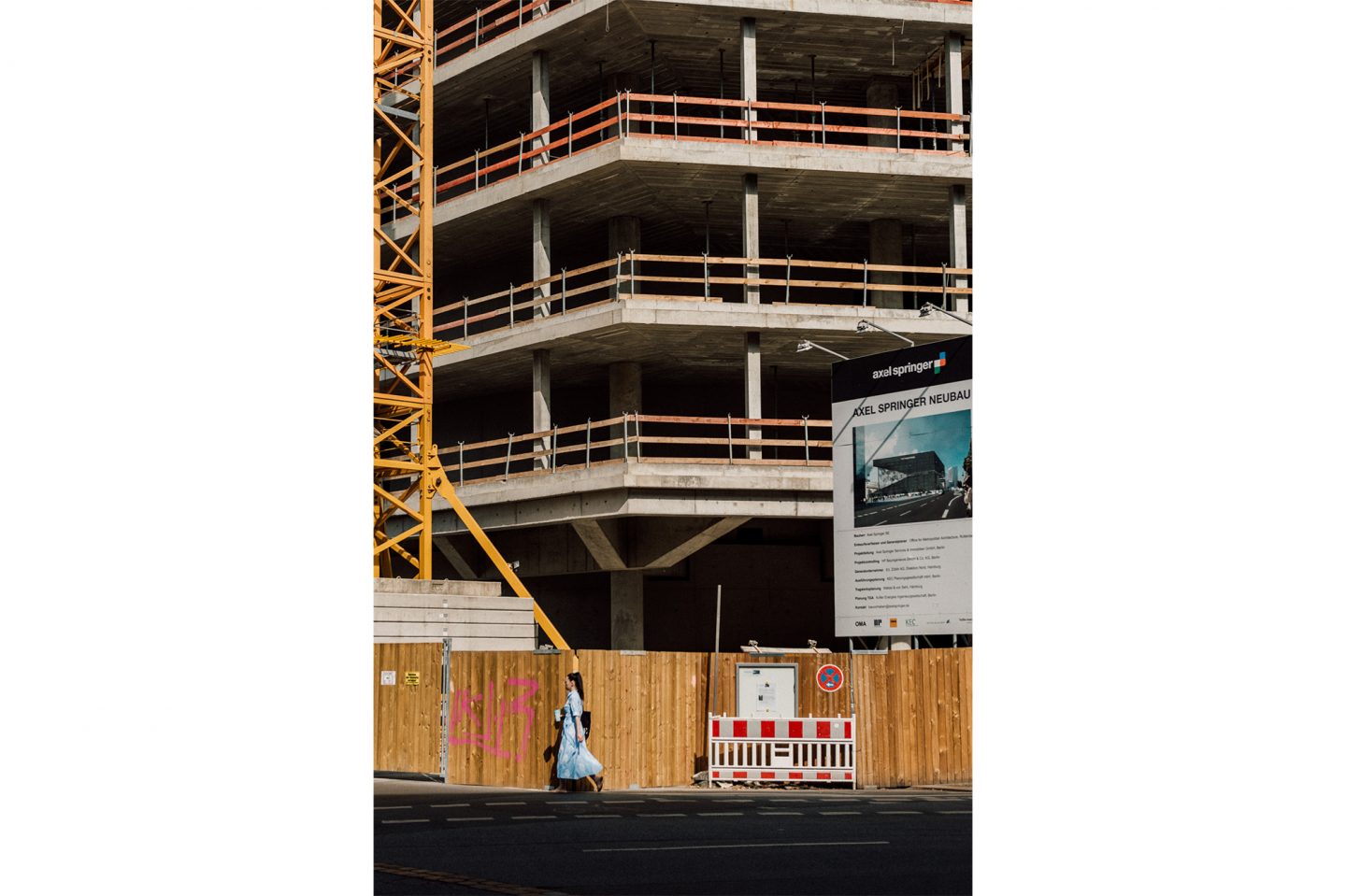

Conversely, the Axel Springer Campus that sits upon the death strip between Kreuzberg and Mitte is being transformed in a historically conscious way by OMA and Rem Koolhaas. Here, the course of the wall will be represented by a void that traces its way through the building. This vast inner atrium symbolizing not only the division of Berlin but — as it houses the very nucleus of the paper, the newsroom — the democratic heart of a city intent on growing together. “One of our favorites is the Axel Springer Campus extension,” explains Putz. “Here, the wall creates a diagonal void through the building, what was the death zone before is now the atrium — the big buzzing newsroom of the new digital area of newsmaking. It’s beautiful symbolism not only spatially and urbanly in the city, but it’s also beautiful symbolism of something that was dead becoming mostly alive.” The variety of approaches to the space seem indicative of Germany’s ongoing struggle for a cohesive, reunified identity. Each asking: to connect or separate, to remember or forget, to reconstruct or metamorphose completely?

“Something that we have learnt during this project is that you cannot ignore the way that people feel,” Willemeit explains, “you need to look to them, speak to them, and try to understand where these feelings are coming from.” The German Pavilion’s video installation ‘Wall of Opinions’, does just that. Director Maria Seifert and cinematographer Helge Renner traveled to the border walls in Cyprus, Northern Ireland, Israel and Palestine, America and Mexico, North and South Korea, and the EU’s external border at Ceuta. The premise of this element of the project was to illustrate, without the burden of academia, the emotion that surrounds these walls. “When we talk about walls, perhaps it is worth remembering that they start in peoples’ heads”, Krückeberg explains, “So we interviewed people at six different sites around the world where walls are erected — or where they will be, or where they have been for a long time — and the first debates there were as to whether or not these walls should come down.” Here, without external commentary, the words of those whose lives are affected by these walls are given center stage.

“In Korea and in Mexico, a lot of people said that one day they hoped this wall would come down like it did in Berlin.”

Birthler, whose work as both a revolutionary and then Federal Commissioner for the Stasi Records has revolved around the psychological un-building of the Berlin Wall, expressed the optimism for a wall-less future communicated by those who were interviewed. “Many of them mentioned what happened in Berlin as being their hope,” Birthler tells us. “In Korea and in Mexico, a lot of people said that one day they hoped this wall would come down like it did in Berlin.”

As such nationalism and subsequent protectionism become ever more virulent, the German Pavilion is laying bare national history to illustrate the danger of such divides. “It’s beautiful because it is the German Pavilion in the biggest international architecture show that exists — and it is a very German topic, and it has relevance in an international context”, Krückerberg explains. “When we started out in Braunschweig when we were in our early twenties it was ’88, and I think 99 percent of Germany was sure that the wall would exist forever.” He pauses, “Basically the message is that this can turn around, if you want it to. We were all surprised how quickly it went in Germany, and that it went without bloodshed… We’re saying there is hope. But even within that hope, be aware — we did it, and that wall cast long shadows. Unbuilding is a process. A long process.”

The German Pavilion’s ‘Unbuilding Walls’ opened at the Venice Architecture Biennale on the 25th of May, and will be on show until the conclusion of the festival in Venice’s famed Giardini.

Cover image and exhibition images © Jan Bitter

All other images © Daniel Müller for iGNANT Production