The Secret History Of London’s Isokon Building

- Images

- Jean-Philippe Woodland

- Words

- Anna Dorothea Ker

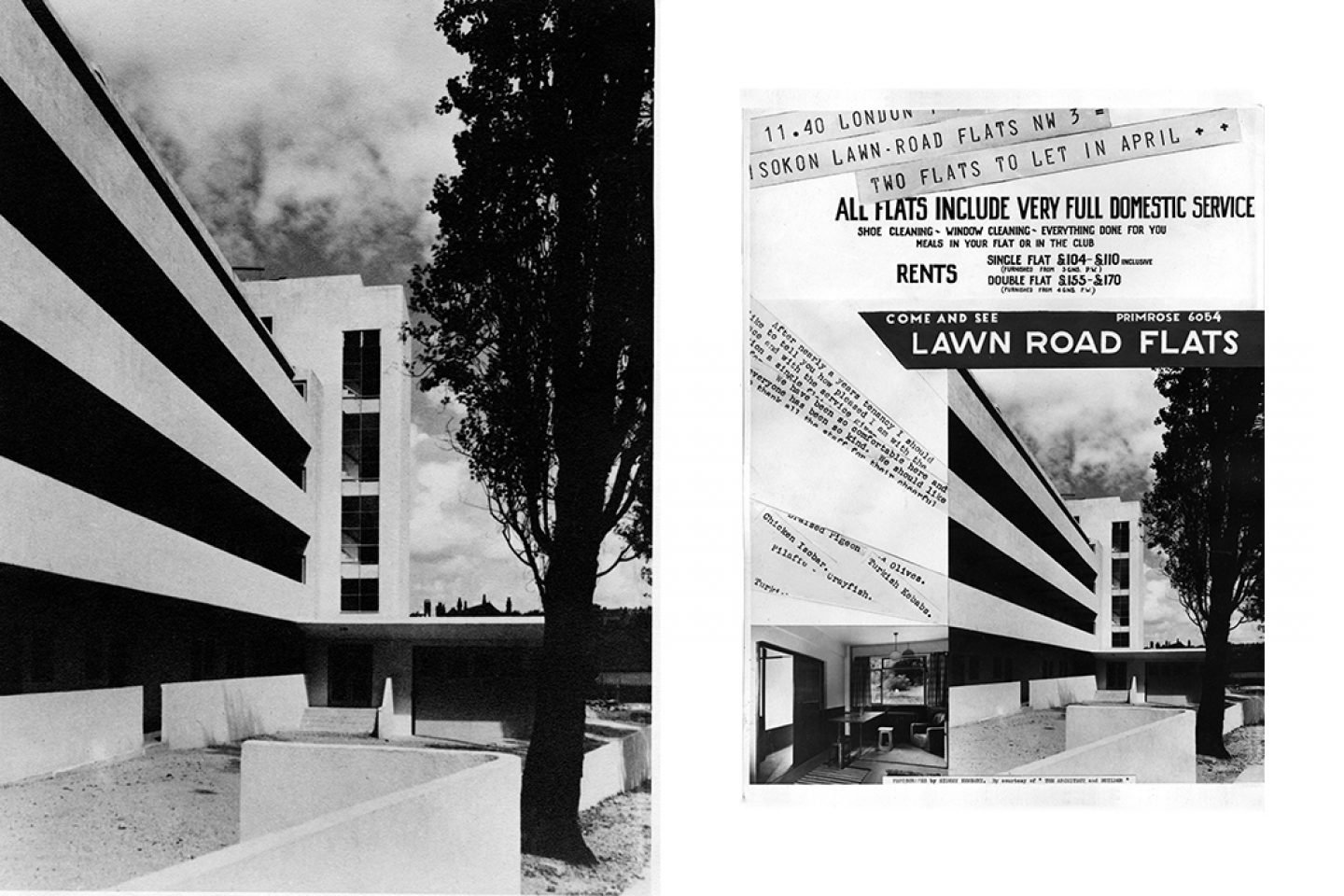

Tucked away in a quiet corner of North London are the Lawn Road Flats, a sculptural Modernist apartment block that was once home to Walter Gropius, Agatha Christie and Soviet spy Arnold Deutsch. The understatedly-named building also goes by the name of Isokon – a title which holds within it a riveting yet little-known legacy of progressive ideas for architecture, design and urban society.

Established in 1934 as one of Britain’s earliest examples of Modernist architecture, the Isokon’s narrative begins with a design firm of the same name, founded by Jack and Molly Pritchard and architect Wells Coates. Their debut project was to design an apartment building and its interior based on the principle of affordable, communal and well-designed inner-city living.

From the underrated potential of plywood to Penguin books, we delved into the Isokon’s rich story with Magnus Englund, Director of the Isokon Gallery Trust and owner of designer and furniture retailer Skandium. During a tour of the building’s gallery and the penthouse apartment in which he resides, he shared with us the multifaceted, fascinating and ever relevant story of Isokon.

The Isokon building was opened in 1934 as a one of Britain’s first block of Modernist flats, and an avant-garde experiment in communal urban living. In what ways was Isokon progressive for its time?

Britain was architecturally very conservative at the time, and the few architects building in the Modernist style were mainly immigrants; Ernö Goldfinger, Berthold Lubetkin, Erich Mendelson. Serge Chermayeff and Isokon architect Wells Coates – who was Canadian – were all foreigners. Maxwell Fry and FRS Yorke were one of a handful of Modernist architects here that were actually British born. Most had been building private, exclusive villas for rich industrialists in a style close to Le Corbusier, so a block of flats with communal service elements like cooking and cleaning was radical. But it was not a working class building – it was aimed at intellectual, working middle class people.

Can you tell us the story behind the building’s name?

“The name arrives from Isometric Construction Drawing, a 3D-looking type of architectural drawings popular at the time.”The name arrives from Isometric Construction Drawing, a 3D-looking type of architectural drawings popular at the time. By spelling it with a K, it got a certain Russian ring to it, like in the word Constructivist architecture (Konstruktivismus in German). Both Molly Pritchard and Wells Coates later claimed that they came up with the name. For the Pritchards though, the building was always called Lawn Road Flats, and Isokon was always the furniture company. It’s only been called the Isokon Building since 1972. But they did build a bungalow in Suffolk in 1963 that’s called Isokon. It’s a very Scandinavian looking house.

Can you tell us more about the origins of the Isokon design company, and how the Lawn Road Flats building came to be?

Jack Pritchard worked as Marketing Manager for Venesta (short for Veneer Estonia), the world’s largest plywood manufacturer at the time – a company with offices across Europe. He was tasked with finding new uses for plywood; until the 1920s they had mainly made tea chests for importing tea leaves from India, hat boxes and food containers. They also made furniture. Jack hired Le Corbusier to design a trade fair stand at Olympia in 1929 (Le Corbusier sent over Charlotte Perriand) and later Wells Coates did another stand. Coates had also used Venesta plywood extensively when he did the interiors for the new BBC building in Portland Place, just north of Oxford Circus. Jack & Molly were politically left wing, interested in modern education, and increasingly interested in modern architecture. Together with Coates, they formed Isokon, with the idea of building modern houses and furniture. But during the building process Jack and Coates fell out over money as Jack could not raise enough capital, and Coates also had a romance with Molly which probably didn’t help relations. At the opening on July 9th, 1934, Molly didn’t mention Coates’ name in her speech even though he was there.

Historic images © Edith Tudor Hart / Philip Harben / Isokon Gallery Trust

The building’s list of former residents includes Bauhaus members [Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer, László Maholy-Nagy] Soviet spies [Arnold Deutsch] and authors [Agatha Christie]. Can you tell us more about the creative community fostered in and around Isokon?

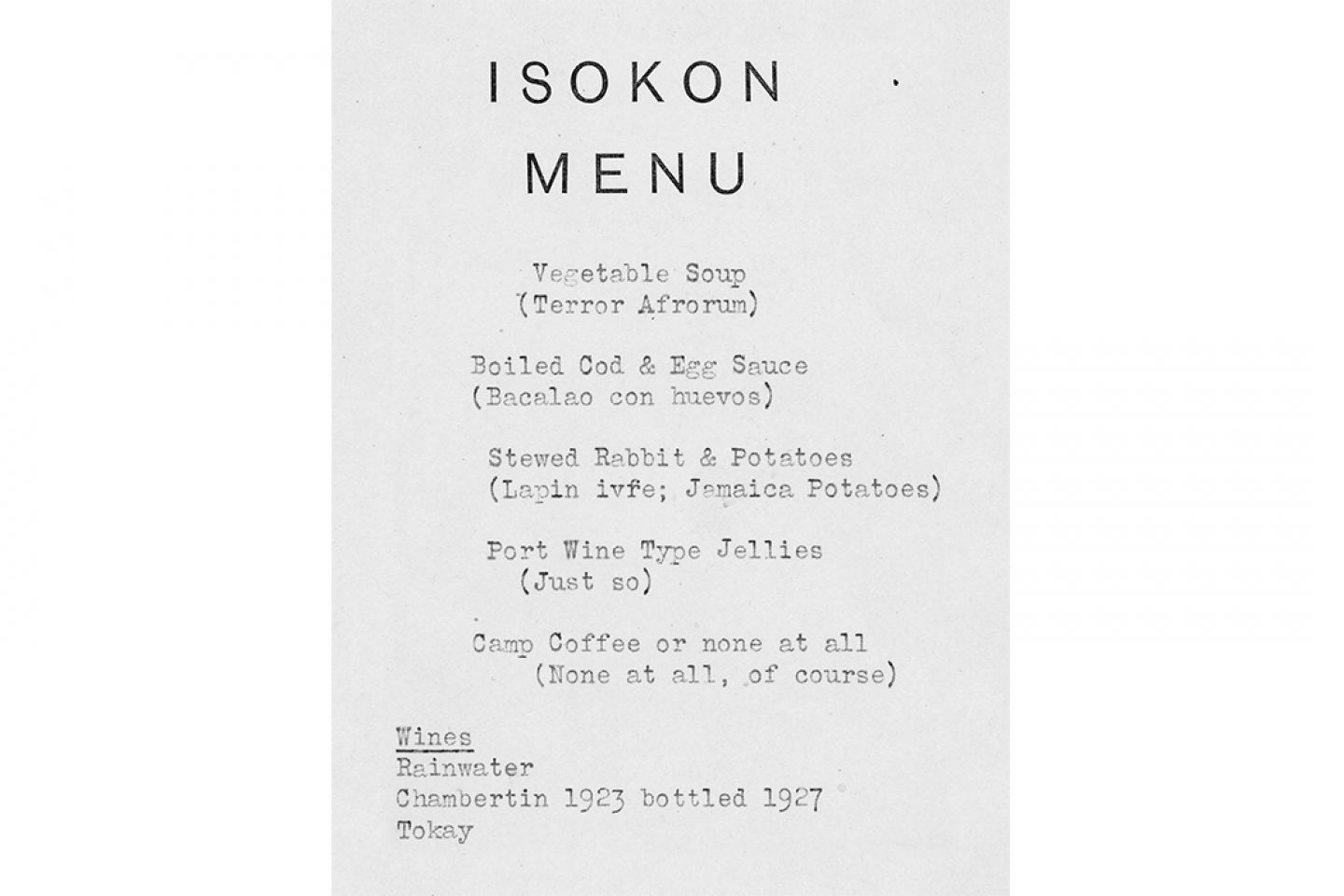

“At least four documented USSR spies lived in the building in the 1930s.”Jack kept an exact list of all tenants until 1964, so we’re lucky to know who lived in which flat and when. Very few pre 1945 tenants do not have a Wikipedia entry. There was an element of Jack only offering flats to interesting people, but also that characters who agreed with his views gravitated towards it. Then it’s also the fact that Hampstead at the time was the British center for left-wing intellectuals; the Freud family lived here, George Orwell, Piet Mondrian, Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson, Henry Moore etc, the list just goes on and on. In 1937 Jack asked Marcel Breuer to convert two of the staff flats on the ground floor into the famous Isobar and restaurant, open for tenants and their guests. He also started a supper club called the Half Hundred Club, where 25 members could invite 25 guests.

The standards of wine and food were very high; the first Isobar manager Philip Harben later became Britain’s first TV celebrity chef. They put on art exhibitions at the Isobar and the discussions must have been fascinating. As late as 1964 they had a Russian month where the Soviet embassy – which was located nearby, and so is Karl Marx’s grave – provided vodka and a former Red Army cook. But Jack was not a communist, he was a left-wing Democratic Socialist and writes in his memoirs how boring communists were to talk to. Having said that, at least four documented USSR spies lived in the building in the 1930s.

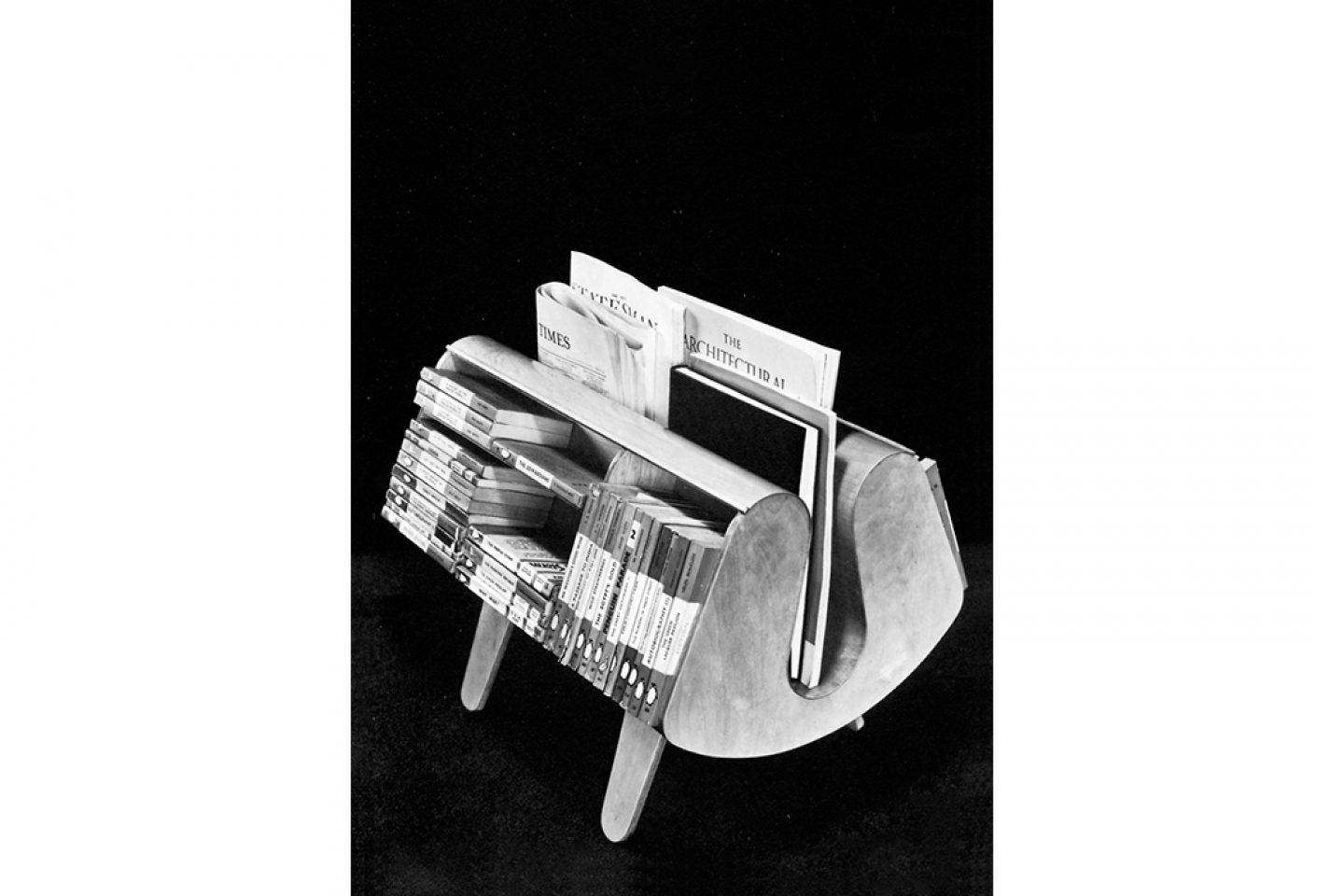

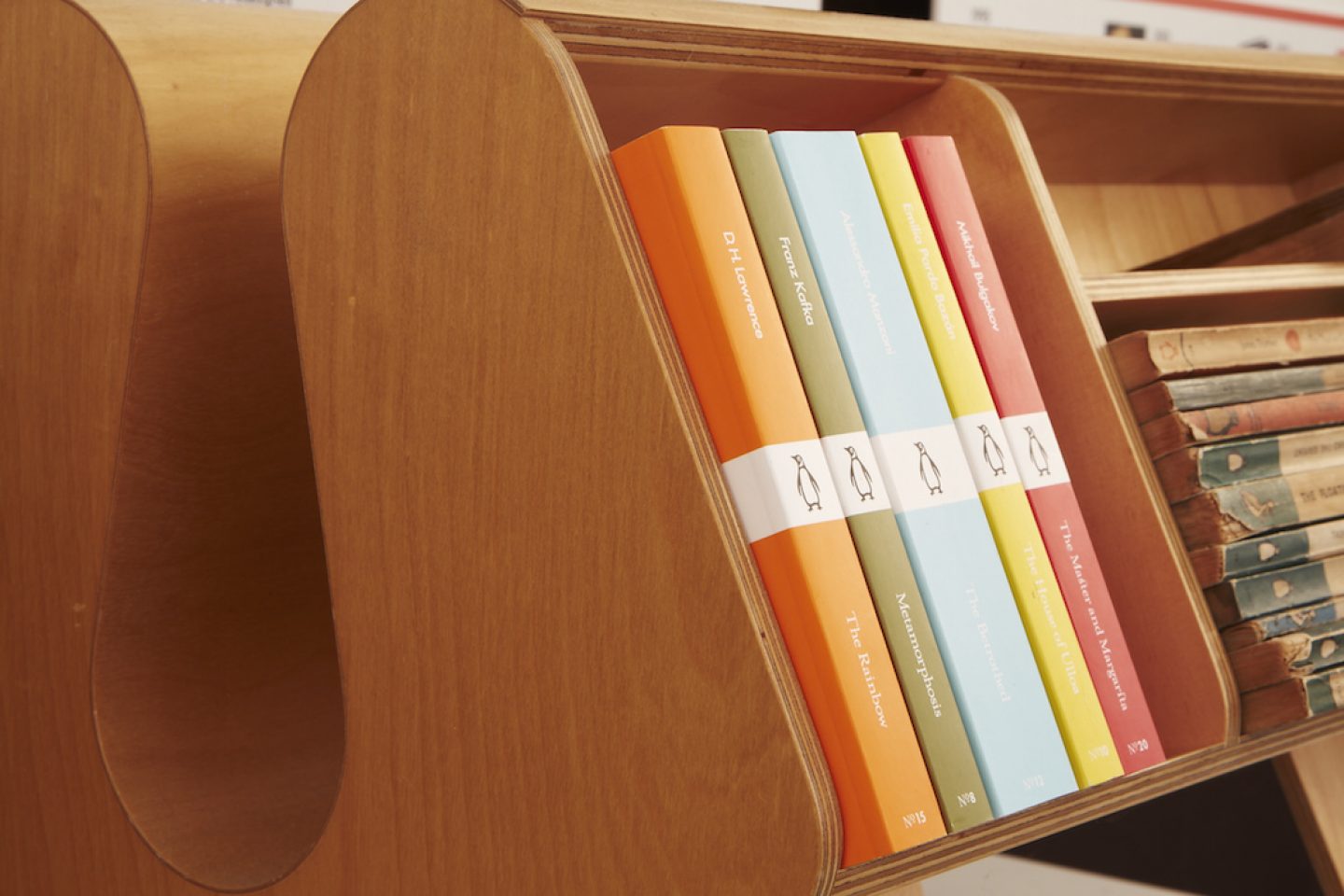

Close-ups of some of the most iconic Isokon furniture designs, on display in the gallery situated on the ground floor.

The furniture branch of the original business continues today as Isokon Plus, currently based in East London. What are some of your favorite pieces, both classic and contemporary?

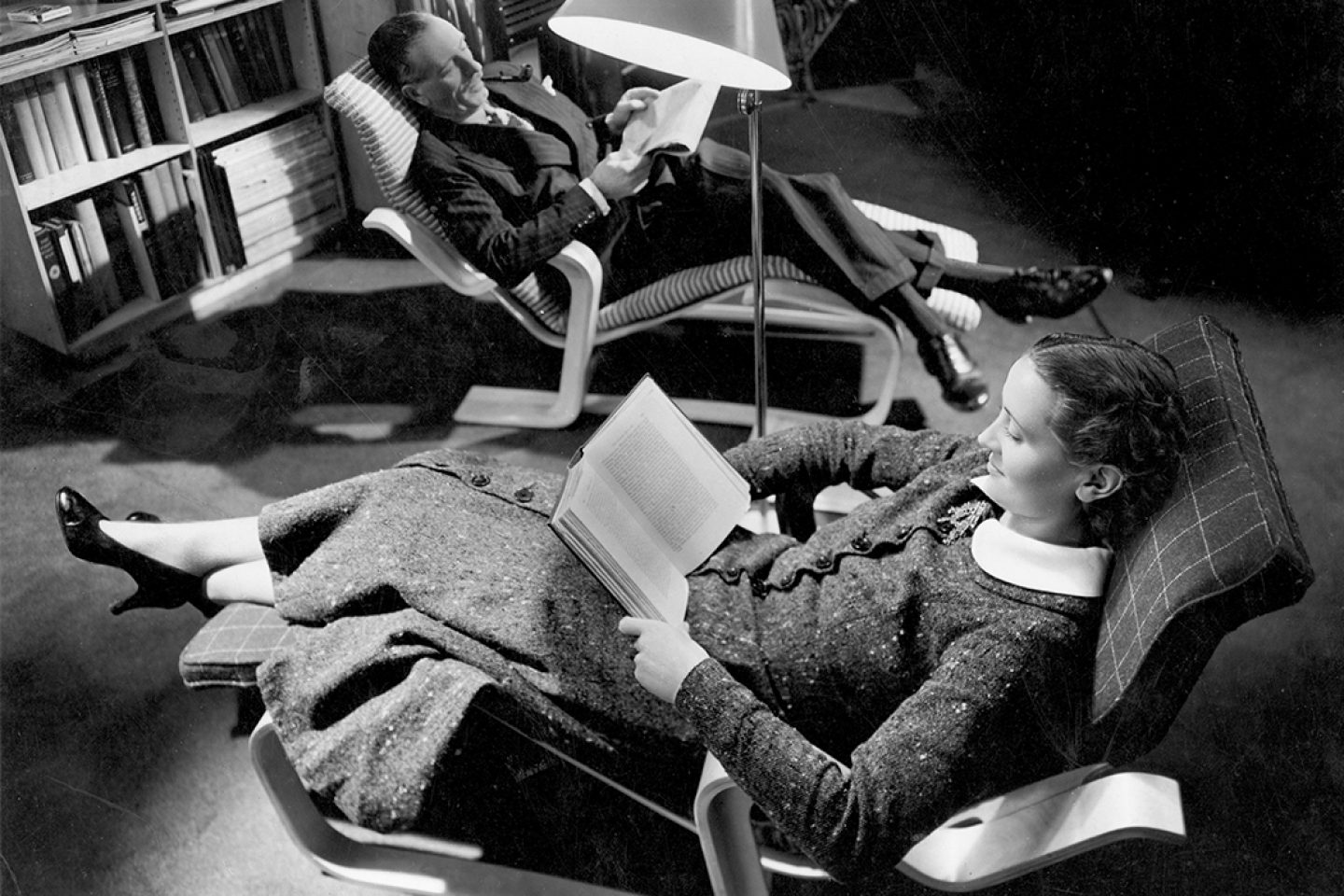

Chris McCourt, who owns Isokon Plus, met Jack in the mid 1980s, a few years before Jack died, and got the rights to make the furniture. The most charming historical piece is the Isokon Penguin Donkey I from 1939, designed by Austrian émigré Egon Riss. But the historically most significant piece is the Long Chair by Marcel Breuer from 1937 as it’s the link between Breuer’s 1920s Bauhaus steel furniture and what he did later in the USA. In the late 1990s, Chris McCourt was contacted by two RCA students, Ed Barber & Jay Osgerby, who wanted to make a plywood table. Chris tried to make them go away as he was tired of students ‘using’ him, but they insisted, and the rest is history. All the early Barber & Osgerby designs were made by Isokon Plus and they even had their first studio at Isokon Plus. Their Loop coffee table is great. It looks simple but is hard to make, and is both 1930s and modern at the same time. They later made their Loop desk for Cappellini based on this first design.

The landmark building was renovated by Avanti Architects in 2003-2004. What were the main challenges – and resulting features – of the restoration?

The building was sold in 1969 to a political magazine called the New Statesman that Jack liked, and then Camden Council bought it in 1972, and spent no money on upkeep, so it deteriorated very quickly. After it was listed Grade I in 1999 – the same protection status as Buckingham Palace – Camden Council came in for lots of criticism and in the end they sold it to Notting Hill Housing Trust on the condition of a restoration plan drawn up by Avanti Architects who have renovated most of Britain’s significant 1930s Modernist buildings. By the time of the renovation only two people lived there, together with rats, owls and pigeons. The kitchens and bathrooms still had 1930s fixtures, and the old cork insulation inside the walls had either dried out or rotted. So they had to remove everything loose and strip it back to the bare concrete, and start again. It took 18 months and was completed in 2004. Now there are 36 flats, plus the large garage where we have a museum. Sadly the Isobar is no more – it was closed in 1969.

You live in the building’s largest apartment on the top floor, which was once occupied by its founders. Can you give us a brief overview of the design and layout features of the apartment?

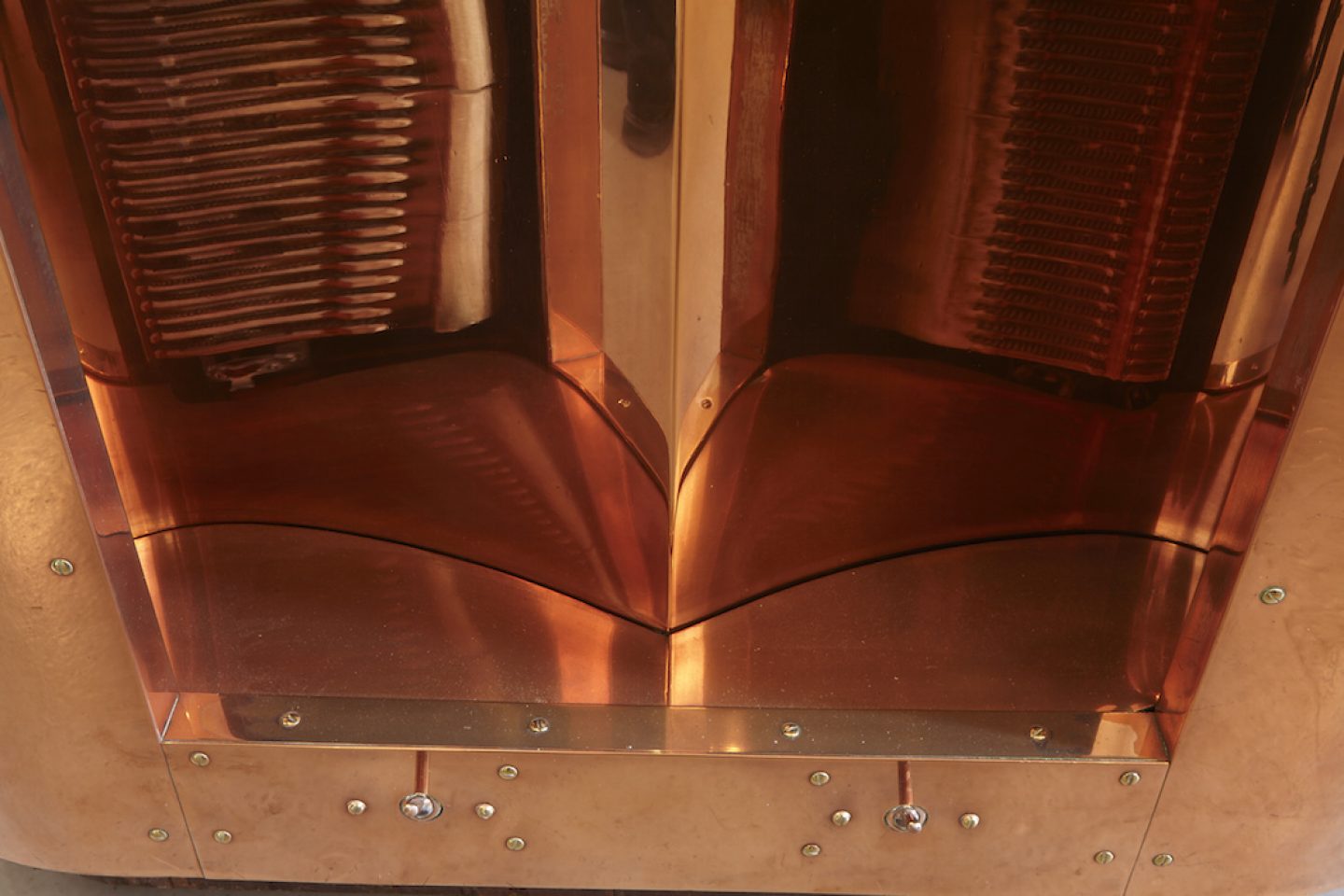

Jack and Molly Pritchard stayed in this flat from 1934 until the mid 1970s. Most of the walls and the floor is covered in Venesta birch plywood from Estonia that has become cigar box brown over time. It’s not huge – the bathroom, bedroom and kitchen are tiny and with the living room it’s only 65 m2. But then it has the flat roof as its 100 square meter terrace, so in the summer we have a fantastic outdoor space, with a nature reserve on one side. In 2014 my wife and I got married on the terrace, just like Jack and Molly’s son Jonathan did in 1955. Like all flats in the building it’s cold, damp and draughty, and five floors up without a lift, but then it was an experimental building and you would not want to live anywhere else. We get a lot of visitors, including the Coates and Pritchard families. It’s also a beautiful part of London with Hampstead Heath on our doorstep and lots of beautiful architecture around – mainly Victorian but with a few Modernist gems like Ernö Goldfinger’s home nearby, which is now a National Trust museum.

What continued significance does the Isokon legacy have today?

Two major things come to mind. There is a major housing crisis in London today where most new built housing is large speculative luxury flats for foreign investors who often leave them empty and wait for them to increase in value. This has doubled the average house prices in London in just a few years. At the same time, there are more single households than ever who need small but well designed spaces with a creative, living community – exactly what the Isokon provided. Secondly, we have the biggest movement of people fleeing war since WWII in Europe, many who are desperate to come to Britain. Jack was personally involved in trying to get passports and work for many fleeing Hitler, and I think he would be appalled by what we’re seeing today with people trying to get out of Syria and Iraq.

"There are more single households than ever who need small but well designed spaces with a creative, living community – exactly what the Isokon provided."

The Isokon Building

Lawn Road

Hampstead

London NW3 2XD

Every Saturday and Sunday 11am–4pm

From 5 March 2016 until October

Photography © Jean-Philippe Woodland