Child’s Play: With INDERGARTEN, Yellow Nose Studio Returns to First Principles

- Name

- Yellow Nose Studio

- Images

- Clemens Poloczek

- Words

- Anna Dorothea Ker

When Berlin-based design duo Yellow Nose Studio first removed the K from ‘kindergarten’ to name their evolving collection of objects, they opened more than a typographic space.

They also proposed an approach to making – close to the spirit of Friedrich Froebel’s original kindergarten, with its emphasis on learning through play and experimentation. What began as a way to explore through building, stacking and removing by hand has become an open-ended method for making – and for life at large.

Early Days

The idea was seeded, quite naturally, at home. By following the discoveries of their young daughter, Muyi, studio founders Hsin-Ying Ho and Kai-Ming Tung found their own way of seeing transformed. Observing Muyi’s instinctive curiosity led them to embrace an open, responsive way of working that would come to shape their entire practice.

If there is often talk of life imitating art, here the reverse unfolded: their art began to follow the observations of life, as experienced through young eyes. As Froebel wrote, “Play is the highest expression of human development in childhood, for it alone is the free expression of what is in a child’s soul […] the plays of childhood are the germinal leaves of all later life.” It is this ethos that anchors Yellow Nose Studio’s evolving creative process, which moves fluidly between process and possibility.

A Practice Built on Play

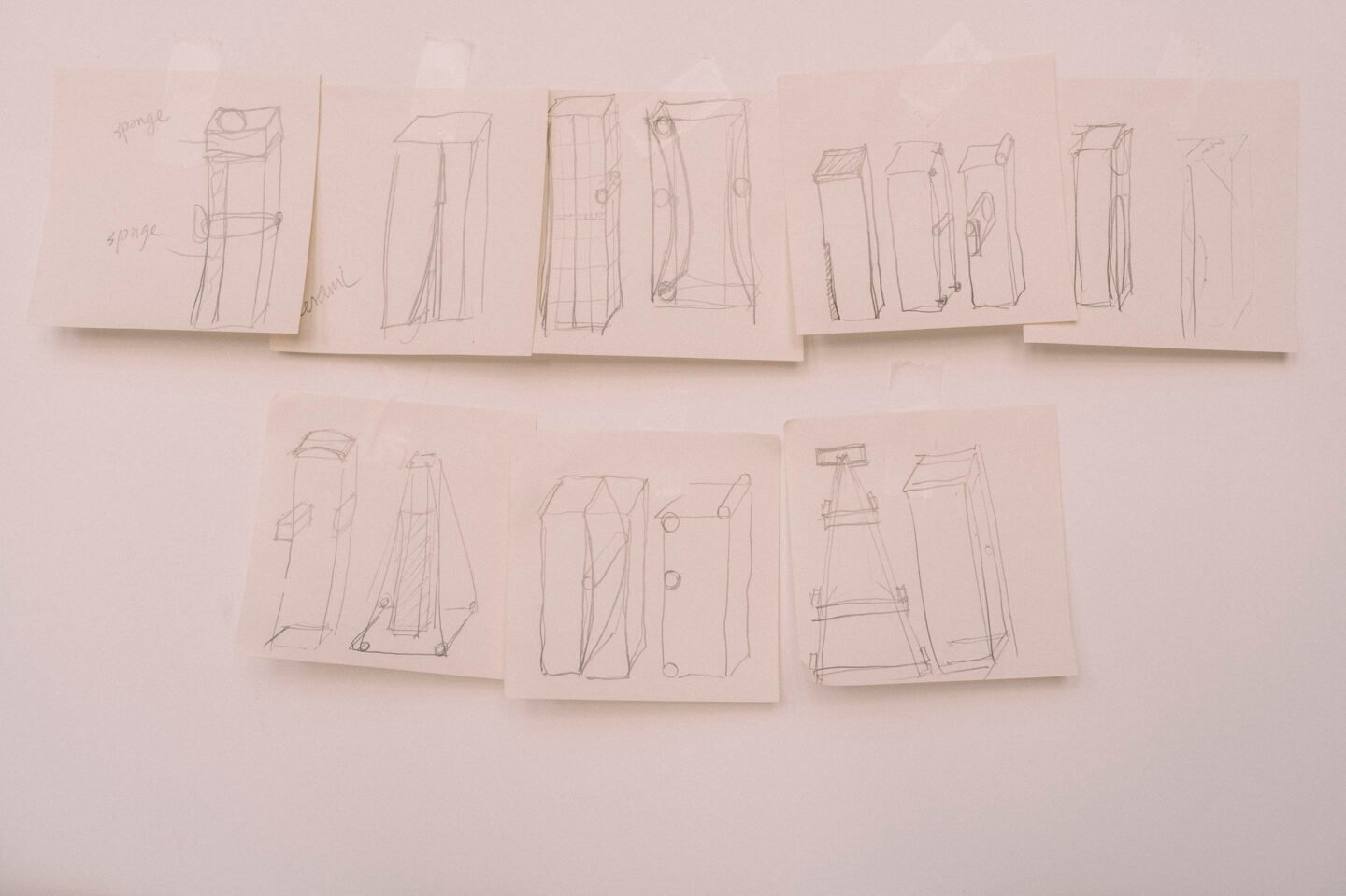

The debut INDERGARTEN collection appeared in a double bill of shows in 2023: a solo presentation at Pon Ding in Zhongshan, Taipei, and a smaller iteration at its satellite gallery, Mini Pon Ding, couched within Pharos Coffee in Jimbocho, Tokyo. At each location, ten variations on three primary forms – the circle, square and rectangle – shaped an open collection of seating objects and vases that crossed boundaries between design, craft, art and architecture. A slender monograph, published with Meter Books and featuring photography by Daniel Farò and graphic design by Hello Me Studio, soon followed.

For Ho and Tung, the project was a way to articulate the focus of their practice. While many first encounter Yellow Nose Studio’s work through its ceramic tableware, the publication revealed the heart of their practice: an experimental process in which wood and ceramic interact, shaping forms that move between art, craft, beauty and function. “It’s really about how we can be playful again, like children,” Ho says. “We want to create designs that feel playful and open.”

Back in their Berlin studio, this involved stepping back from strict logic. “At first, we tried to build everything symmetrically and rationally, but when a piece is slightly off, it becomes more exciting.” A daily ritual emerged. “We play with the offcut wood like building blocks, stacking them up and breaking them down again each day,” explains Tung. “It has become a kind of morning ritual for us.”

The process, which can take up to two hours daily, resists certainty, opening space for accident and intuition. “It really goes by feeling. Sometimes when we push something and a piece falls, that moment feels right,” says Ho. “When we first picked up the offcut wood, we realized how relaxed and free the process could be,” she adds. “That changed our design mindset to something more intuitive.”

The Origins of INDERGARTEN

Ho and Tung’s method continues to morph, its ideas grown from daily life. “Our starting point is usually a feeling or a story. It could be our child, exhibitions, travel or objects we encounter.” Muyi’s point of view and rapidly evolving learning stages continue to shape their thinking. “Recently, the main inspiration has been seeing through her eyes – how she uses things, how she perceives color,” Ho says. Through this lens, new subtleties become visible. Familiar objects reveal unexpected qualities, and basic assumptions about function and use are upended.

This questioning carries through in their physical approach to making. “When we create new works, we think like sculptors. We add and take away at the same time. If the project needs function, we add that at the end,” Tung shares. Every piece must satisfy both practical and conceptual concerns. “Form and function are equally important to us. The pieces need to have both.” Making is collaborative at its core. “When we create, we always do it together. For example, with the chair series, we each made ten pieces, then swapped and deconstructed each other’s work, adding new elements until we agreed on the final ten,” Ho explains. “It’s important to us that each piece contains both of our perspectives.”

A Second Field

In 2025, Yellow Nose Studio extended the INDERGARTEN collection with ‘A Second Field’, presented at LICHT Gallery in Tokyo. The opportunity to exhibit arose through an organic exchange with LICHT’s founder and director, Mitsuo Suma, who had first seen their work at Mini Pon Ding. Later correspondence led to an invitation. “Mitsuo-san was very supportive and open-minded,” reflects Ho. “He told us to just create what we wanted to create, with no restrictions.”

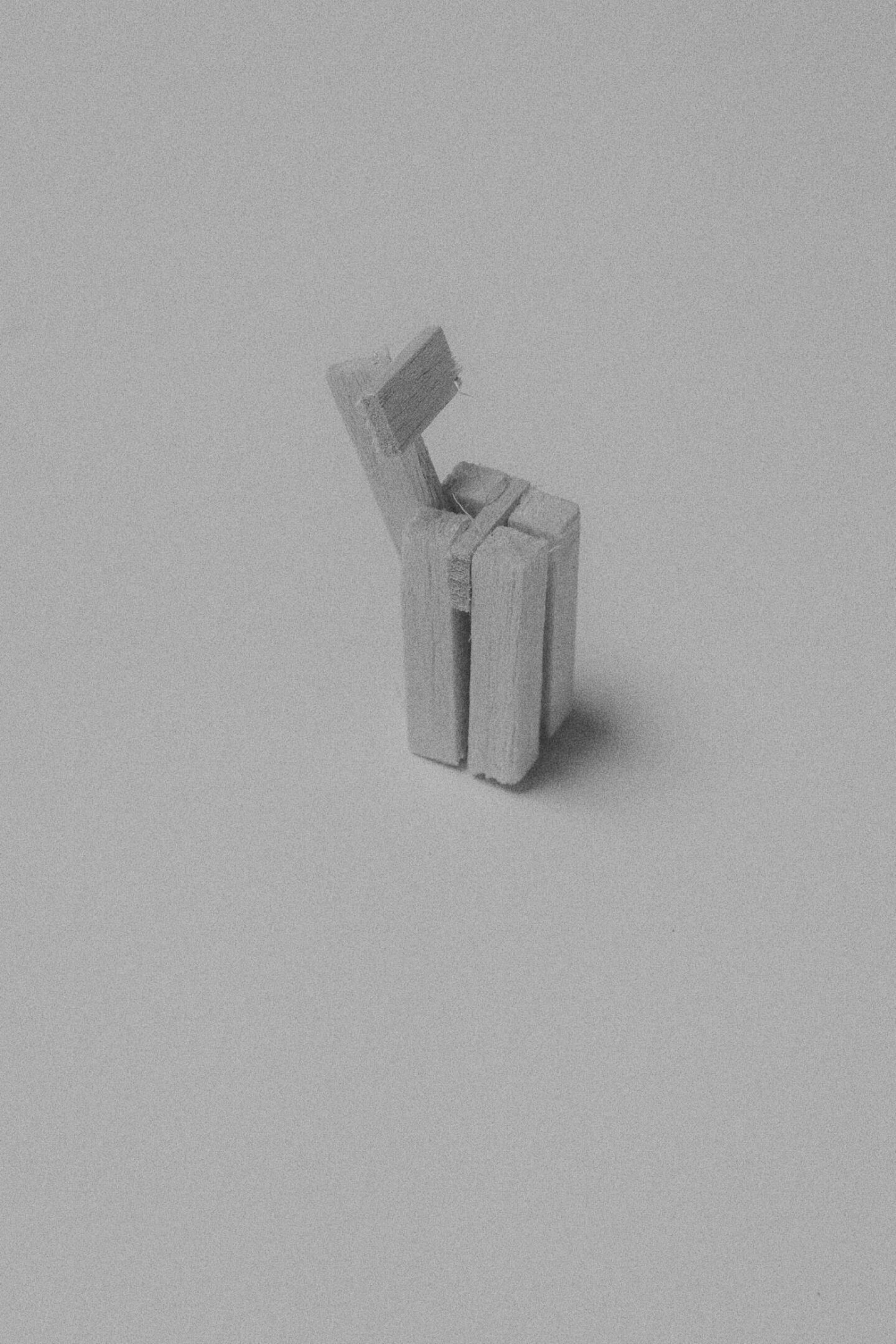

Building on their earlier explorations, this new body of work deepened their process of intuitive making: “a return to stacking, arranging and imagining without instruction.” The pieces became simpler and more distilled. “The work has evolved. Even though we kept the same concept, the pieces we designed became simpler.”

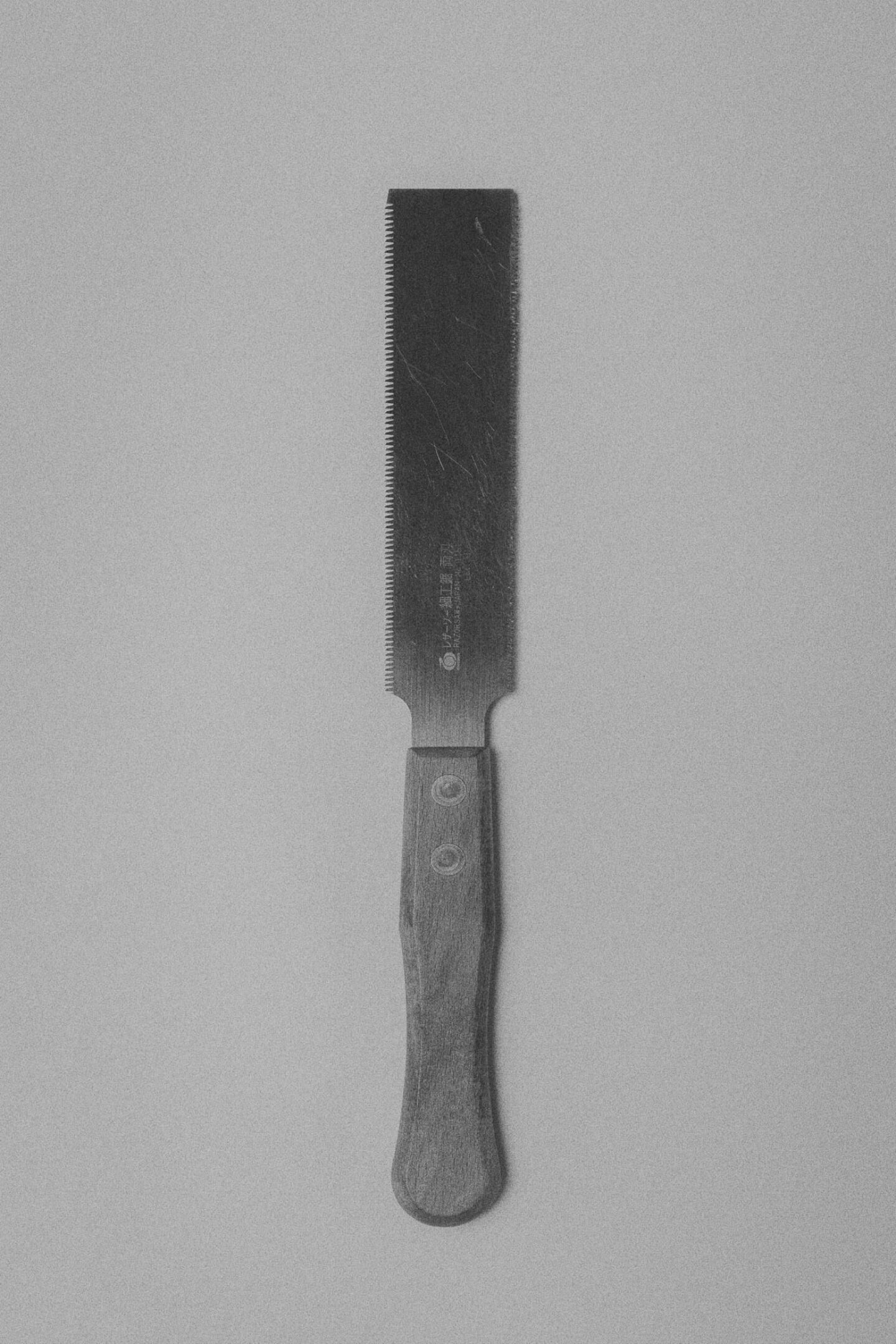

The 1,2,3 Chairs embody this shift. “We used one type of wood, solid spruce, and stacked it. The simplicity came from Muyi starting to count, which is where their names come from.” The materials reflect this clarity. “For ‘A Second Field’, we worked with spruce, cedar and beech to see what ideas we could create.” Ceramics entered the conversation in a Tetris-style configuration. “We combined the materials, fitting the ceramics exactly to the size and height of the wood.”

A palette of natural tones emerged from close observation. “We developed around 20 new colours for the ceramics, inspired by the sky in Berlin,” Ho says. The wood – sourced in standard columns of 10×10 cm and 8×8 cm available at German building supply stores – was left raw and unembellished to highlight the beauty of its natural grain.

Altogether, the exhibition at LICHT brought together 20 pieces – “50 percent old works, 40 percent new, and 10 percent exclusive pieces” – across adult-sized 1,2,3 Chairs, modular side tables and puzzle-like wall objects. Suma chose to display the works on plinths composed of concrete, stone and carpet, creating a tactile setting that stepped away from the sterility of a white cube and nodded to the pair’s architectural backgrounds.

Growing the Dialogue

Unlike most exhibited works, visitors are strongly encouraged to touch and sit on the Yellow Nose Studio’s objects. Engagement through tactility remains key. “We want people to try the pieces and discover the playfulness.” The 1,2,3 Chairs are intended to provoke curiosity, prompting viewers to question the essence of the chair as an object – “we wanted people to experiment with how to sit on them,” Tung explains. Their inquiry remains grounded in physical experience. Ultimately, the pair wants their work to circle back to essential questions: “What is design, what is function, what is a chair?”

Through INDERGARTEN, Ho and Tung continue to open new pathways – not only for the future of their own work, but for ways of thinking about design itself. “We hope that our work prompts questions and new possibilities – we would love to see curators imagine these ideas evolving into bigger-scale projects,” Tung says. As Ho adds, “We’ll follow the same process and see where it leads.”

Images © Clemens Poloczek | Text: Anna Dorothea Ker