What Is An Original? A New Exhibition By The Bauhaus-Archiv In Berlin Explores The Complex Nuances Of Production And Reproduction

- Name

- Bauhaus-Archiv

- Project

- Original Bauhaus

- Images

- Alexander Kilian

- Words

- Rosie Flanagan

“Creative activities are useful only if they produce new, so far unknown relations”, wrote László Moholy-Nagy in his 1922 text Production – Reproduction.

“In specific regard to creation, reproduction (reiteration of already existing relations) can be regarded for the most part as mere virtuosity. Since it is primarily production (productive creation) that serves human construction, we must strive to turn the apparatuses (instruments) used so far only for reproductive purposes into ones that can be used for productive purposes as well.”

Questions surrounding production, reproduction and purpose enwreathe the Bauhaus, a school whose radical teachings bound art to industry. In celebration of the 100th anniversary of the institution’s founding, a new exhibition by the Bauhaus-Archiv / Museum für Gestaltung at the Berlinische Galerie draws upon the nuances of Nagy’s statement through 1000 artefacts – originals, reproductions, reissues, and contemporary commissions – that explore the school’s immaterial heritage and continuing influence.

“To me, the title ‘original bauhaus’ is intentionally ironic, because the Bauhaus produced chairs and objects for everyday life – so what is an original?” asks exhibition curator Nina Wiedemeyer. “Of course, if it’s presented in a museum, then it must be an original,” she says with a wry smile.

Rather than being organized chronologically, ‘original bauhaus’ is structured around 14 case studies: one for every year that the Bauhaus ran until it was forcibly closed by the Nazis in 1933. “The Bauhaus is no monolith, it’s very diverse, and we chose very subjectively 14 stories from this huge universe”, Nina explains. “We didn’t want to show everything, but to unfold these cases carefully.” From Moholy-Nagy’s question of Production – Reproduction, to topics like Revivals, Unity in Diversity, Unique Works in Series, Writing History and Family Resemblances, each section approaches the Bauhaus through a unique lens, offering insight to the institution as both a movement, and perhaps more interestingly, as a school.

One of the case studies is Marianne Brandt’s tea infuser; a diminutive piece that never entered production, which Nina describes as having a “fierce intensity”. Brandt was the first female student to work in the Metall-Werkstatt at the Bauhaus; a department that she would later go on to lead. It was during her time studying at the Weimar campus that she handmade eight almost-identical infusers, whose iconic geometric forms were – like a vast majority of Bauhaus pieces – intended for mass production. The exhibition features seven of the eight originals, delivered from collections around the world, and which are displayed together for the first time at the Berlinische Galerie.

“We wanted to show her work in the context of her apprenticeship”, Nina explains, gesturing to a shelf where the implements used to create the tea infusers sit quietly. This contextualizing and recontextualizing is present throughout the exhibition, and offers insight into a more structural side of Bauhaus education. “The Bauhaus as a school is central to the exhibition”, Nina enthuses. “They had incredible teachers, experts who taught the preliminary courses; and that is particularly important, because today people think we don’t need art in our schools. This exhibition argues that yes, yes we do.”

“People think we don’t need art in our schools. This exhibition argues that yes, yes we do.”

The Bauhaus’ famed preliminary courses introduced the basic principles of art and design using experimental education methods and common materials. The mandatory six-month course was initially devised by Swiss painter and art teacher Johannes Itten, who ran the classes from 1919-1923. László Moholy-Nagy took charge of the courses between 1923 and 1928, shifting the focus from artistic to technical issues in art and design. In 1928, Josef Albers, who had led the preliminary course alongside Moholy-Nagy in the years prior, became the official head of the course. What is most interesting about the preliminary courses, aside from the innovation they facilitated and the minds that initiated them, is that unlike the rest of the Bauhaus they were only partially documented.

“The library at the Bauhaus-Archiv is really incredible,” Nina tells us, “you have thousands of books, monographs, and exhibition catalogs, but there was no workbook. We wanted answers to some very simple questions: What did those teachers tell their students? What were their tasks? What kind of directions were they given?” Over two years, she undertook extensive research into this neglected area looking for answers, traveling to the Albers Foundation in Connecticut and the Getty Institute in Los Angeles, “looking at all of these fragile pieces of paper and trying to collect directions from them”.

This monumental block of research unfolds beautifully in ‘original bauhaus’, where the results of the preliminary courses are given as much precedence as the works of the masters who facilitated them. On show are the results of Wassily Kandinsky’s ‘Color Circle’ exercises, and Johannes Itten and László Moholy-Nagy’s ‘Material Studies’. “Half of these works here have never been shown before, because previously people were not so interested in these half-drawn drafts, they were only interested in those objects that already looked like architecture or art”, Nina tells us. “But for me, there is a high art in these directions, and in these fragile things.”

“But for me, there is a high art in these directions, and in these fragile things.”

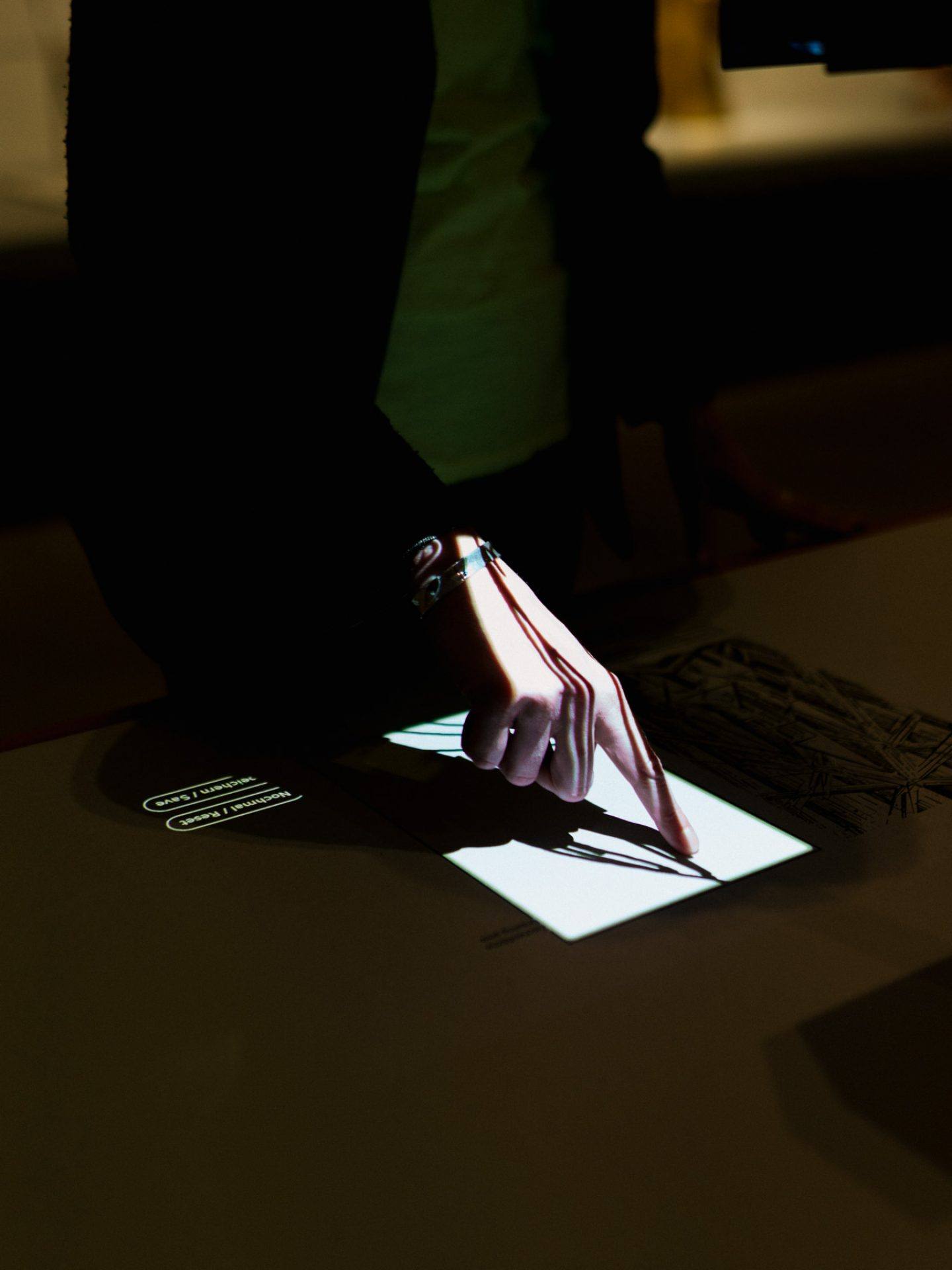

The nature of the preliminary course is playfully enacted through an interactive installation that sits at the heart of the Berlinische Galerie. Berlin-based design studio Syntop was commissioned to create a digital workplace where visitors could try their hand at a selection of exercises from the Bauhaus’ preliminary program. “We didn’t want to have a simple reenactment, but something that worked for a digital time”, Nina explains, as she traces the outline of a zebra with her finger at one of the stations. “We worked really hard to make something that is simple and accessible that is based in practice”. The other commissioned works are equally considered, emphasizing the exhibition’s overarching theme and giving contemporary context to the school and its influence.

One of these works, a photograph of the Bauhaus in Dessau’s stairwell by Renate Buser, towers over the exhibition as it pays homage to Oskar Schlemmer’s famous ‘Bauhaustreppe’ (1932). Whilst Schlemmer’s “original” remains hanging at MoMA in New York, other iterative works adorn the walls of the Berlinische Galerie. Amongst them, the draft that Schlemmer made before the painting, the copy that his brother Casca Schlemmer painted for their family in 1958, Delia Keller’s photograph ‘The Bauhaus Staircase’ (2000), and Brian O’Leary’s interpretation ‘Study for Senta Clinic Mural’ (2015). Together, these pieces illustrate the complexities of production and reproduction. Though all are deeply referential, they are also – as Nina points – out undeniably, originals.

While the wash of celebratory shows this year have rendered some Bauhaus topics banal through familiarity, by including case studies that are both iconic and hitherto unseen, ‘original bauhaus’ offers an enlightened and prismatic overview. “Each chosen piece had to have a story that was interesting to tell,” Nina explains of the curatorial premise, “one that gave broader access to the scene, and didn’t repeat the same story, but had another angle, because for me it’s not important to say: ‘We will tell you what an original Bauhaus is!’, but to instead say: ‘We have 14 answers to this question, and we’re not telling you which is right, you have to go and see for yourself’.”

ADDRESS

Berlinische Galerie

Alte Jakobstraße 124-128

10969 Berlin

OPENING HOURS

Wed-Mon: 10.00-18.00

Closed on 24.12.2019 and 31.12.2019

The centenary exhibition of the Bauhaus-Archiv und Museum für Gestaltung, ‘original bauhaus’, is funded by the Senate Department for Culture and Europe in Berlin, and the German Federal Cultural Foundation. ‘original bauhaus’ is showing at the Berlinische Galerie from the 06.09.2019-27.01.2020.

Text by Rosie Flanagan | All images © Alexander Kilian for IGNANT production