Daniel Hölzl Reimagines the Architecture of Endings with ‘soft cycles’ at Berlinische Galerie

- Name

- Daniel Hölzl

- Project

- soft cycles

- Images

- Clemens Poloczek

- Words

- Rosie Flanagan

In the work of Daniel Hölzl, every ending is a nexus for new beginnings. His practice unfolds through recursive gestures—recycling, reconstitution and transformation. Through soft sculptures that give the hard edges of our built world fluid form, and petroleum-based composites that carry deep time and fossilised life, Hölzl explores impermanence and the cyclical nature of existence.

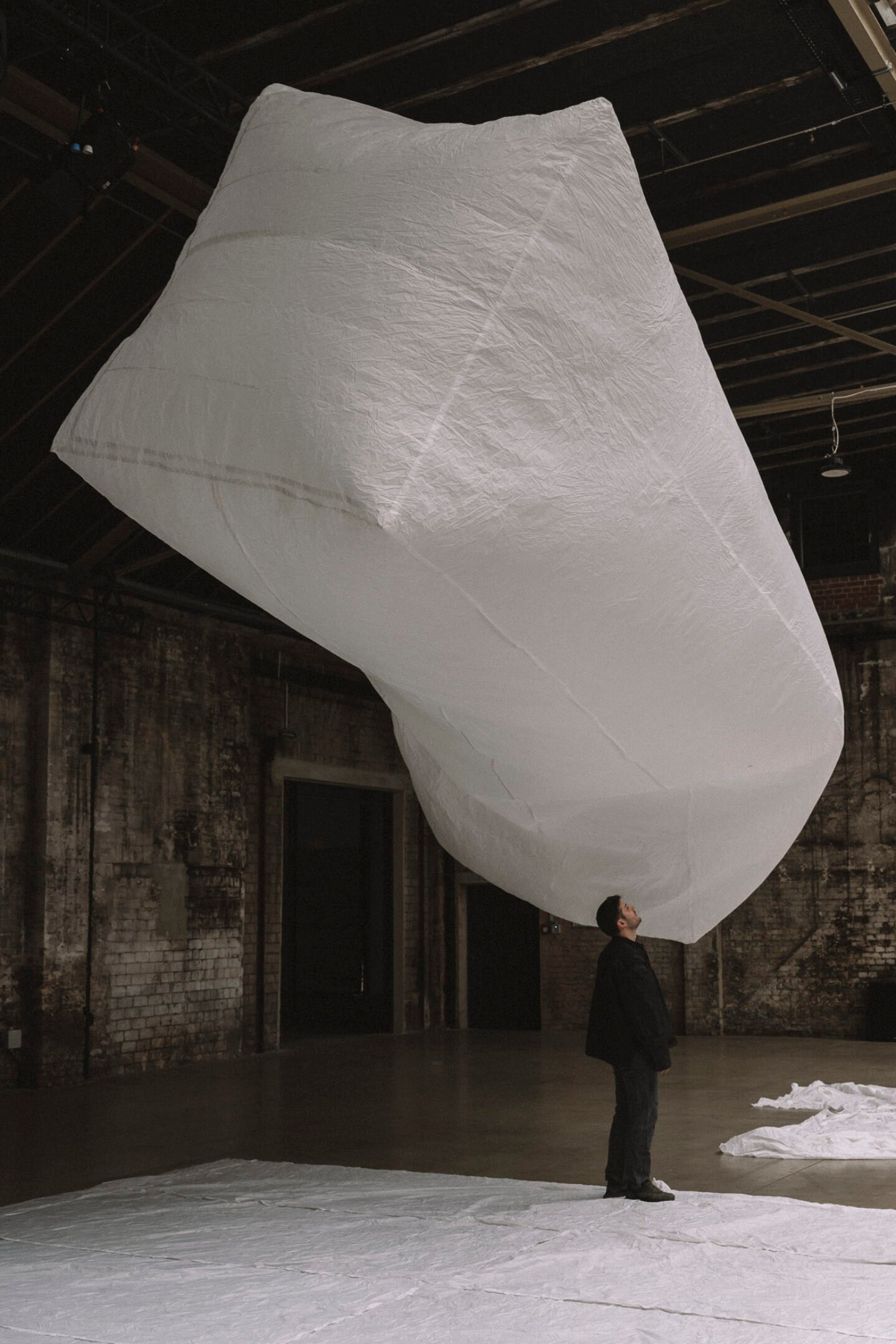

We meet when the sun is still high above Berlin. It’s early evening, and Hölzl has come straight from the Berlinische Galerie, where he’s spent the day installing soft cycles — a site-specific intervention commissioned to mark the museum’s 50th anniversary. A once empty space on the rooftop is now occupied by a monumental inflated cube that holds a second, luminous and shifting shape inside. Composed of “borrowed” materials—past works made from parachute silk, old seams on display—the internal volume billows up and out, growing taller and taller until it pushes against the very edges of its transparent confines. Emptied of air, it collapses. And then, a breath of life begins the process once more.

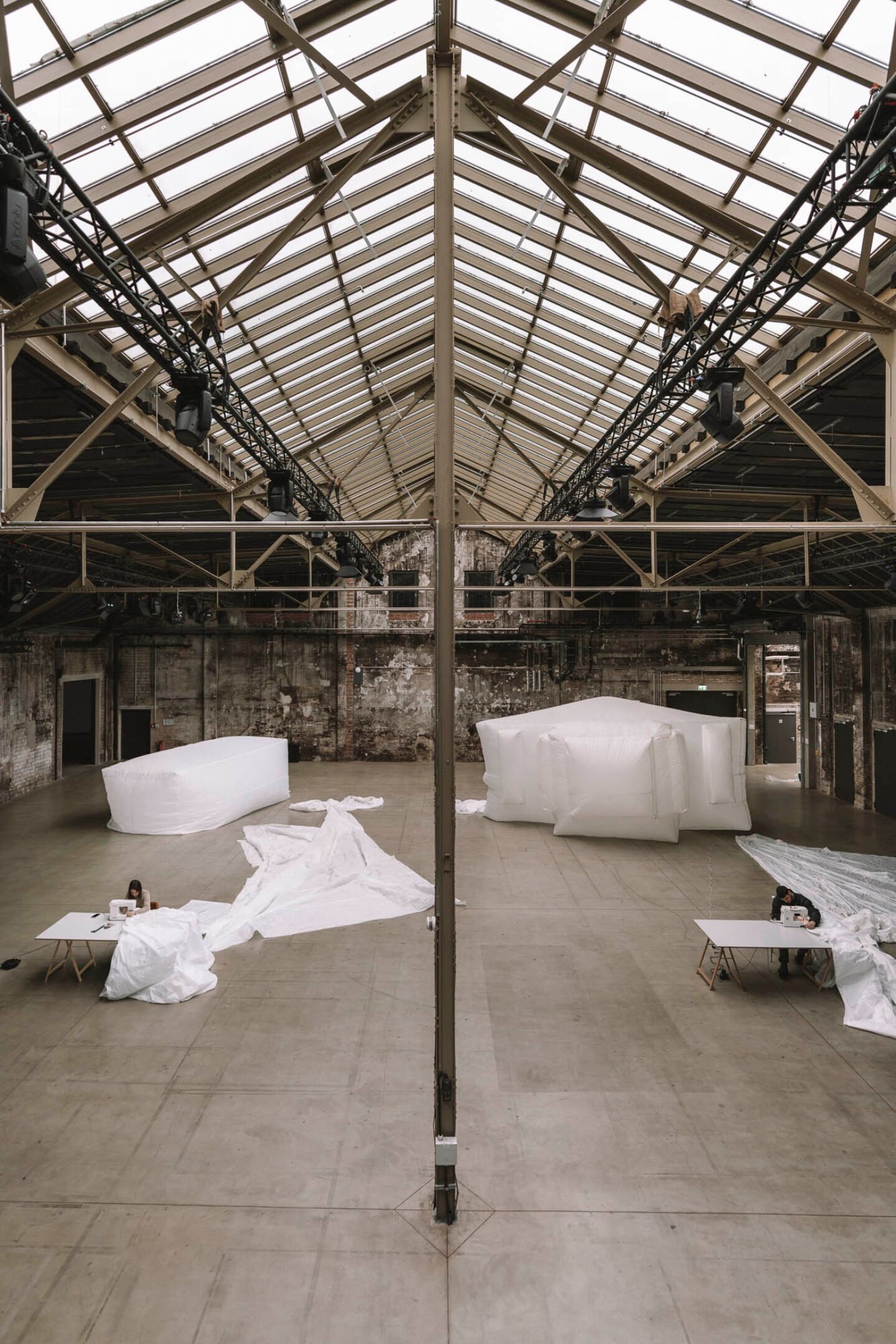

This rhythmic new work draws together nearly a decade of material inquiry—the interior volume once eight different works, each one deconstructed and reimagined to create this new spatial composition. In the vast expanse of Wilhelm Hallen, Hölzl used digital modeling and physical encounters with these works to guide his selection of the soft-architectural fragments—doors, windows, alcoves—that would form the luminous palimpsest at the heart of ‘soft cycles.’ In conversation with Ignant, the artist reflects on this transformation and layering as it relates to the broader philosophical and material underpinnings of his work. Using the Ship of Theseus as a framework to better understand his practice, he explains how resisting the notion of finality offers a peculiar freedom—not in the preservation of form, but in the infinite unfolding of possibility and becoming.

Installation setup of 'soft cycles' at Wilhelm Hallen, Berlin

You seem to be drawn to the cyclical nature of things, where the “end” of one work often signals the beginning of another. In light of this, perhaps the best place to start our conversation is for you to introduce us to soft cycles, your new piece at the Berlinische Galerie.

In many ways, this work is a continuation of older pieces—so to talk about it, I really have to talk about all the others! While I’m considered an emerging artist, I’ve been in Berlin for nine years and have done quite a lot of work in that time. One side of my practice deals with architecture through the creation of these inflatable, light-soft objects that are juxtaposed with the hard and monumental buildings common in the city. The other side of my practice is interested in petroleum-based products: airplane parts, recycled paraffin turned into paint, that kind of thing. These different sides both deal with ideas relating to space, material history, temporality and how everything is connected in some way.

"It’s an inflatable within an inflatable that fills an abstract gap on the top of a museum—almost like the final piece of a puzzle."

The new work is to celebrate Berlinische Galerie’s 50th anniversary. It’s called soft cycles, a name that references recycling and the concept of cycles more generally—of materials, of life, of matter. It’s an inflatable within an inflatable that fills an abstract gap on the top of a museum—almost like the final piece of a puzzle. The piece is in dialogue with an earlier work marked space – unmarked space (2004) by Fritz Balthaus. When they were renovating the building that houses the museum, Balthaus defined new spaces within the architectural landscape, one of which is this empty space. It’s a very clever, very minimal piece of public art.

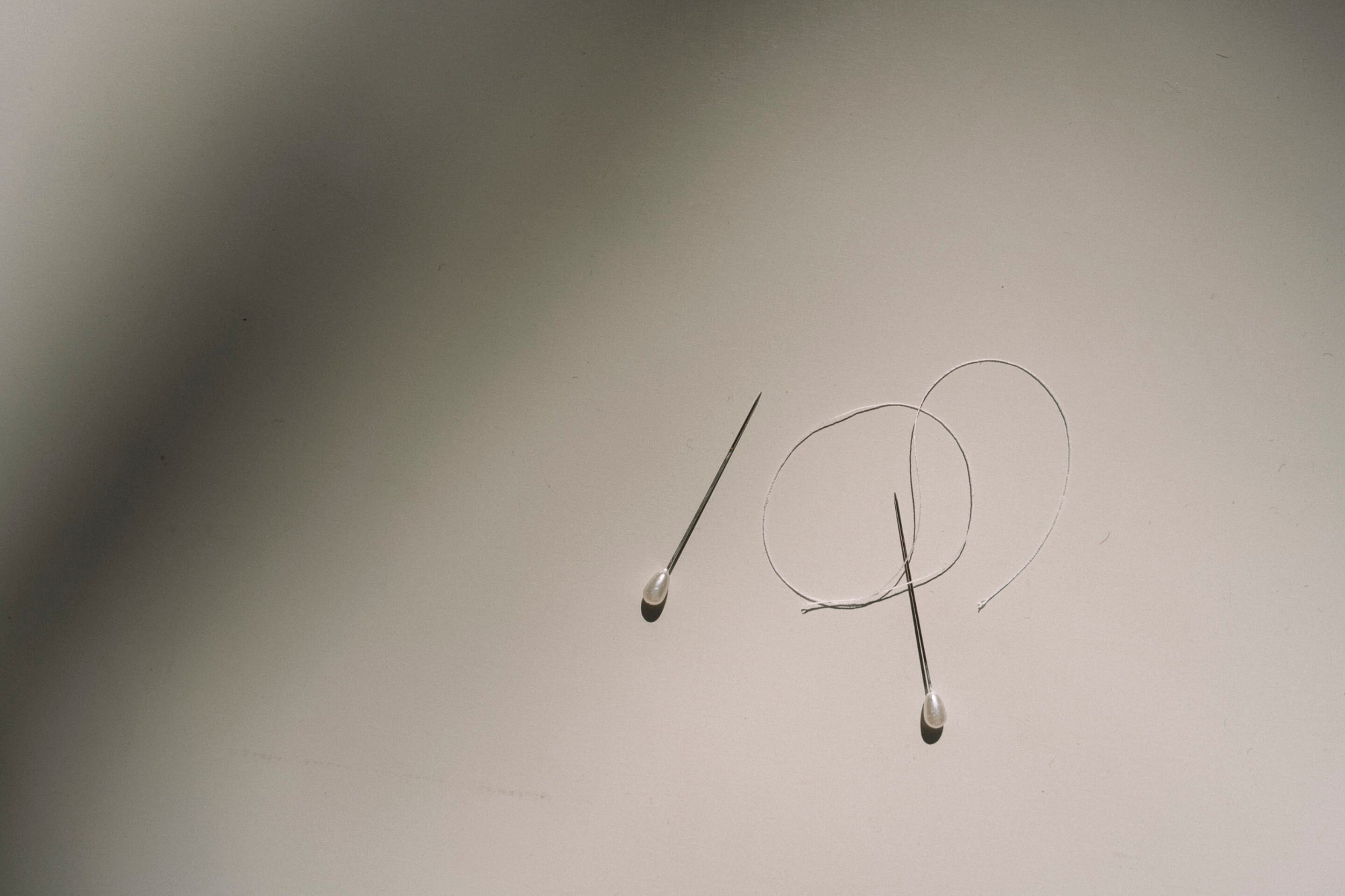

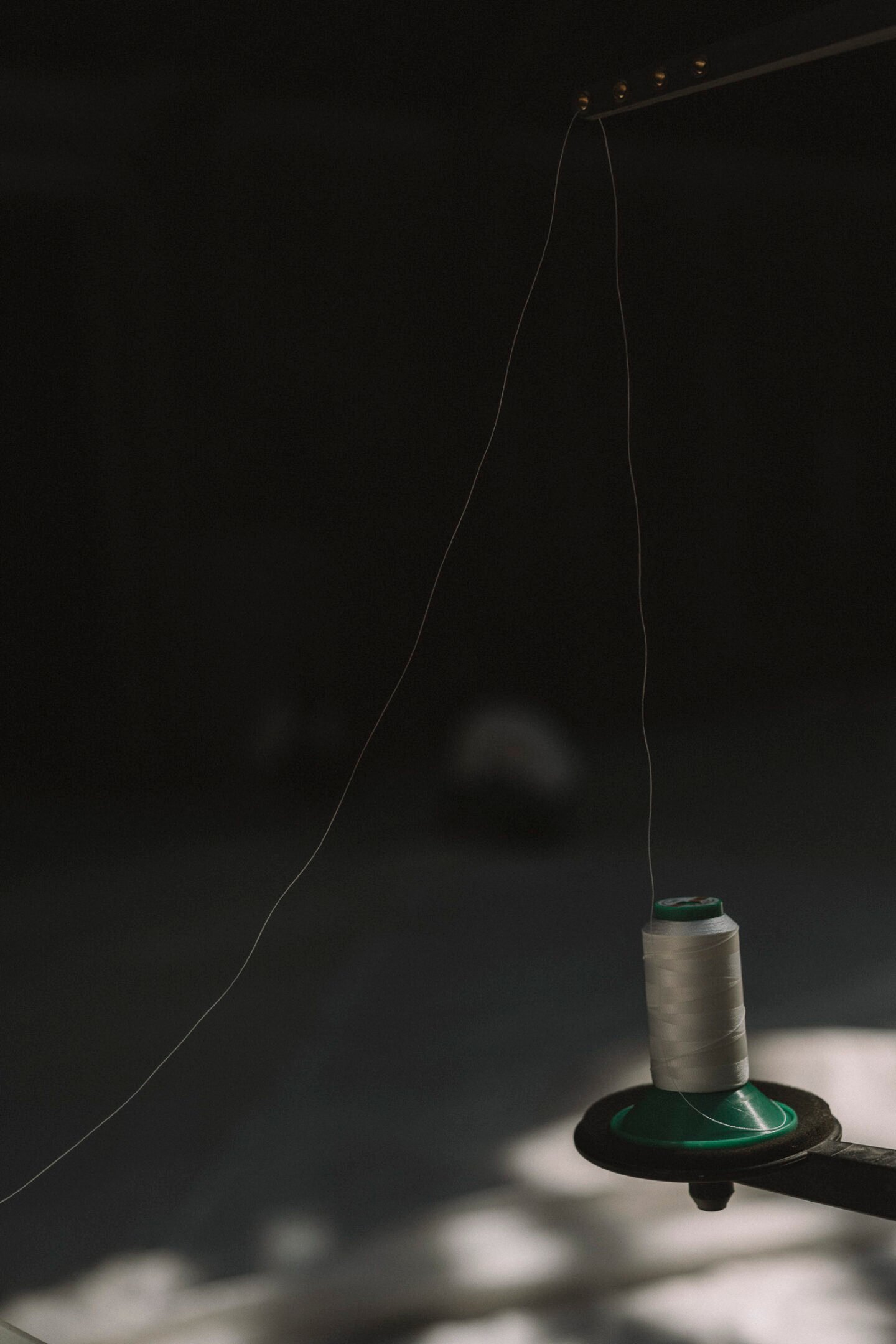

In this space, I’m installing a transparent cube that will be constantly inflated at high pressure. This will house a second inflatable made from parachute silk repurposed from works that have been installed previously across Berlin. These installations all dealt with the architecture of the space that they represented—taking a room and inflating its dimensions out of its window. I disassembled these older works and reconnected the fragments into large panels. The new form they take is very simple, but the beauty is that the old works remain visible—you can see the windows and doorways; all these seams, all these scars, are carried over.

The entire work inflates and deflates in slow motion. As it inflates, the internal sculpture rises—touching the ceiling—before deflating. This creates a rhythmic motion and a crackling sound as it gently touches the boundaries and surrounding walls, almost as if the volume is breathing. It shows architecture falling apart and being resurrected, and falling apart and being resurrected again… This ties into the idea of cycles—up and down, expansion and collapse, growth and decay. Everything, when you think about it, is fluid and temporary. Even permanent monuments will erode over time. Art allows us to have a glimpse of this.

Installation setup of 'soft cycles' at Wilhelm Hallen, Berlin

Could you tell us a little about the process of creation, particularly the way you inflated, deflated and deconstructed past works in order to create the new work at Wilhelm Hallen?

The internal volume was created using eight inflatables that I’ve shown in Berlin over the last nine years. Working on this piece in Wilhelm Hallen was very unique, the space allowed me to inflate all of these works simultaneously—something I’ve not been able to do previously. I spent a lot of time deciding which fragments I wanted to be visible and recognisable in ‘soft cycles.’ Based on my digital model and plans, I marked where I wanted to cut each of the works, sliced them open, and—in a kind of reverse-origami process—flattened them into large panels which I then used to form the central volume in the new work. Now, when you stand in front of the museum and look up at the work, you can see traces of the past—and I think that’s really nice.

"All of my works are driven by an interest in material."

What draws you to work with materials that are engineered for speed, for sailing, for flight, for progress?

I think it’s subconscious really. All of my works are driven by an interest in material. For instance, I participated in a show about coal and carbon. And I thought, carbon fiber is related to this, right? Then I found out that it is actually industrially produced from paraffin. So, paraffin is turned into plastic. Plastic is turned into sheets, and then the sheets go through a machine that eventually turns them into carbon fiber. They literally burn everything away except the carbon, leaving behind these very fragile fibers. But the moment you weave them together and add glue—more petroleum—they become incredibly strong. Without the glue though, they’re nothing. It’s this composite way of working that really interests me.

The moment I read this and realized that carbon fiber comes from petroleum—from fossil fuels—that it’s connected to this whole history of plants and organisms dying, then being compressed over millions of years. All of this, a cycle of millions of years, to eventually become this slimy liquid that then gets turned into so many other things—so many things that it’s almost impossible to speak about them all. And this is my issue: it’s endless, and I am fascinated by this endlessness because I’m interested in the opposite, which is maybe me not wanting to accept the fact that everything has to eventually die, which I’m actually really scared of!

On one hand, this fiber never decays, because, in an elemental way, carbon will always be there. It’s billions of years old. It could even be from the stars. I mean, there’s all kinds of carbon, but the element itself is super, super old. In contrast, you have this very white fluid, paraffin wax. The moment you hang one of my paintings outside, it melts—it gives away its potential, its energy, really quickly. It’s like a candle—you light it, and it’s gone. The other one, though, is never going to be gone. So, I layer and layer these, and somehow the work just keeps going.

Installation setup of 'soft cycles' at Wilhelm Hallen, Berlin

Your petroleum-based works often find new forms in new works after they’ve been exhibited, but your inflatables usually rely on recycled materials from external sources. What prompted you to reuse parts of previous installations in soft cycles?

The museum is celebrating its 50th anniversary—it’s a moment of reflection and retrospect which made this way of working feel especially fitting. Initially, my idea was to create a new inflatable, but the more I thought about it, the more I realized that I had to make this new inflatable from all the inflatables I’d ever made. It felt right for the context and it’s also a much more sustainable way of creating; all of the works were just collecting dust in gallery storage anyway. I mean, I’ve tried showing them elsewhere, but technically, these rooms belong to their partners. It has to be this intimate conversation between the model and the copy, the original and the replica, otherwise it doesn’t quite work.

Do you know the Ship of Theseus? No? It’s a philosophical concept. So, for a thousand years, a guy named Theseus has a ship. Over time, the wooden planks of the ship rot, so he replaces them with new ones. After a thousand years, every plank has been replaced. When does the ship stop being the ship? At some point, all the planks are new, but it’s still the same ship, right? Later, another person asked: What if over a thousand years, we took the rotting planks of wood and reassembled the ship in the museum—but, at the same time, the ship made from the new planks is out sailing the ocean? Now, there are two ships. Which is the true Ship of Theseus? Are they both the original? It’s a beautiful thought, right?

Recently, I looked at my own work and realized that each piece is many things. The installation made from the sails is the installation, but it is also the sails, and the boat the sails came from… you can keep going endlessly, but eventually, you have to give up and accept that maybe the installation is everything and nothing at the same time—or maybe it’s even more. Maybe both boats have the right to be the original. I think that’s the interesting thing with artwork that functions more like performance. For example, a theater piece—when it’s over, it’s over, but we still have the documentation: photos, videos and stories we tell about it. In a way, this happening, and us talking about it, is the only thing that preserves it.

"...you have to give up and accept that maybe the installation is everything and nothing at the same time—or maybe it’s even more."

If I use fabrics from past works to make a new work, the past works still exist in the minds of those who saw them. The past work doesn’t entirely vanish—it’s more that the concept, the story, is what matters. I borrowed the material required to create a new work for, let’s say, two months. Then the material either goes back to the universe, or maybe I borrow it again for a few more months down the line. I mean, all of the carbon I work with will outlive me, so it’s just me taking it, borrowing it for a time before giving it back to the universe.

It was a kind of funny realisation, but one that was quite beautiful because it was freeing. I’m never sad when I recycle something. I’m actually really happy that I have a bit of control over what it gets recycled into, because eventually, that would happen anyway. So it’s kind of the same in a way, and it’s more fun. It keeps everything light while allowing you to talk about really big, scary, beautiful, sad topics. I like that about it. I think that’s what it’s really about.

'soft cycles' installation at Berlinische Galerie

Photos: Clemens Poloczek | Text: Rosie Flanagan | Drone Video: Daniel Hölzl